-

1 of 253523 objects

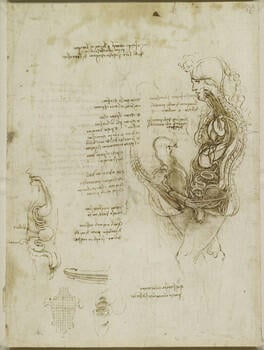

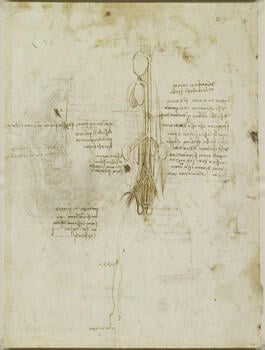

Recto: The viscera of a horse(?). Verso: The hemisection of a man and woman in the act of coition c.1490-92

Pen and ink | 27.6 x 20.4 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919097

-

Recto: an anterior view of the arteries, veins and the genito-urinary system of an animal, probably a horse; a spinal column with notes on dissection. Verso: a drawing of the coition of a hemisected man and woman; a drawing of the left side of a youth, showing the alimentary tract; two sections of the penis and a male torso squared for enlargement; details of genitalia and nerves based on Galenic theories.

The principal drawing on the verso records Leonardo’s early beliefs about conception, as derived from the writings of his forerunners, who differed on whether the process involved a material union, a spiritual union, or both. Plato, for example, recorded in the Timaeus the belief that the ‘seed’ was a spiritual entity in the brain and spinal cord, possessing a will of its own and compelling men and women to procreate. Here Leonardo notes that ‘Avicenna claims that the soul begets the soul, and the body the body’; and elsewhere he recorded that ‘Hippocrates says that the origin of men’s sperm derives from the brain, and from the lungs and testicles of our parents, where the final decoction is made; and all the other limbs transmit their substance to this sperm by means of transpiration, because there are no channels through which they might come to the sperm’ (Victoria and Albert Museum, MS Forster III, f.75r).

Leonardo seems here to depict an arrangement whereby three components are involved in conception. In the male he has drawn channels into the penis from the lumbosacral plexus at the bottom of the spinal column (to transmit an ‘animal’, ie. soul, element), from the heart (a ‘spiritual’ element), and from the testes (a ‘material’ element), thus following Mondino’s division of the body into animal (head), spiritual (thoracic) and material (abdominal) regions. The channels from heart and testes unite with the urethra and pass through one duct in the penis, while the channel from the spinal cord remains separate. A simple dissection would have ascertained that the penis has just one channel. Leonardo may also have believed that his fictive channel in the male between the heart and the testes had a secondary function: the notes include the reminder to consider ‘how the testes are the cause of ferocity’ – as the emotions were believed to be felt in the heart, the tube between the testes and the heart would also allow this ferocity to transmitted from its source.

The arrangement in the female is less clear. The spine bifurcates and a branch of the spinal cord passes directly into the uterus, but the ovaries and heart are not drawn, and it is thus questionable whether at this stage of his career Leonardo believed that there was an equal contribution to conception from the female. He did however introduce a channel from the uterus to the breast, to allow the menses retained during pregnancy to be converted into milk. The main drawing and the subsidiary study to the left also display Leonardo’s crude understanding of the gastrointestinal system at that date. The smaller drawing distinguishes between the small and large intestines, but the coiling of the intestines is abbreviated, and in the middle of the intestines there is a second stomach-like organ (perhaps an exaggerated cecum) connected to the umbilicus; in the notes Leonardo reminds himself to investigate ‘how [the infant] is nourished through the umbilicus.’

Text adapted from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012, no. 2Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Pen and ink

Measurements

27.6 x 20.4 cm (sheet of paper)

Other number(s)