-

1 of 253523 objects

Recto: The gastrointestinal tract, and the bladder. Verso: The gastrointestinal tract, and the stomach, liver and spleen c.1508

Recto: Traces of black chalk, pen and ink. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink | 19.2 x 13.8 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919031

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

Recto: The gastrointestinal tract, and the bladder. Verso: The gastrointestinal tract, and the stomach, liver and spleen c.1508

-

A folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript B'.

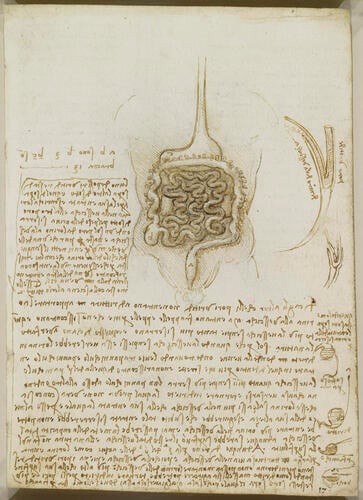

Recto: a drawing showing the alimentary tract and kidneys; the ureter; drawings showing the position of the urinary system in various positions of the subject; notes on the drawings.

The principal drawing is a fine representation of the lower gastrointestinal tract. The stomach is attached (at c) to the duodenum in a human configuration, and thence connected to a somewhat schematised jejunum and ileum, with the kidneys visible behind. The cecum is at b, and the epiploic appendices of the colon are prominent. In the note to the left Leonardo gives the length of the small intestine as 13 braccia (about 7.5 m) and of the colon as 3 braccia (about 1.8 m), only a little in excess of the usual human dimensions.

The remainder of the page is concerned with the flow of urine from the ureters into the bladder. The diagrams at centre right are cross-sections of the ureterovesical valve, which prevents the passage of urine from the bladder back into the ureters; the ureteral lumen does travel obliquely through the bladder wall, but does not double back as sharply as drawn. Leonardo denied the traditional view that, as the bladder filled, pressure on the lumen closed the valve, believing instead that gravity was solely responsible for the flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder; unsurprisingly, Leonardo was unaware of the peristaltic contractions that propel urine along the ureters.

The marginal figures at lower right thus show the bladder with the body in various positions (upside down, upright, lying on one side, and lying on the front), and the long note reads:

"The authorities say that the passages of the ureter do not, in carrying the urine into the bladder, enter straight into it, but enter between one skin and another skin by ways that do not meet each other, and that the more the bladder fills the more they are closed. ... This contention is not true, because if the urine were to rise in the bladder higher than its entrance, which is about the middle of its height, it would follow that this entrance would close and no more urine could enter the bladder, and it would never exceed half the capacity of the bladder. Therefore the rest of the bladder would be superfluous, and Nature makes nothing superfluous. Therefore we shall tell by the 5th [chapter] of the 6th [book] On Waters how urine enters the bladder through a wide and tortuous passage and how when the bladder is full the ureters remain full of urine... If a man lies down it can turn back through the ureters, and even more so should he be upside down... Where a man lies on his side one of the ureters rests above, the other below, and that which is above opens its entrance and discharges urine into the bladder, and the other duct below is closed by the weight of the urine, whence one single duct gives urine to the bladder, for it is sufficient that one of the renal veins should purify the blood of the vena cava of urine.

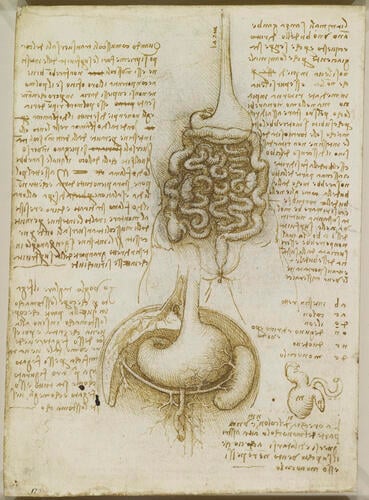

Verso: a drawing showing the arrangement of the intestines within the abdomen; the liver, stomach and spleen; the appendix, caecum and ileocolic junction; notes on the intestines and liver.

The principal drawing depicts the stomach, the duodenum somewhat out of position, the jejunum, and the ileum in a somewhat schematised manner. The course of the large intestine is correct, though the epiploic appendices are not indicated. Attached to the cecum is the appendix, shown again in the detail at lower right – apparently the first depiction or description of this structure in Western medicine. Leonardo suggests that the function of the appendix is ‘contracting and dilating so that superfluous wind does not rupture the cecum’.

In the note to the right, Leonardo posits that the length and tortuosity of the alimentary tract is necessary to slow the passage of food, turning it around as it travels so that all of the food can make contact with the walls of the intestine; if the intestine were straight, gravity would cause the food to pass quickly through the body, and in the note to the right he states that the jejunum ‘is upright and therefore empty’. But in the passage to the left Leonardo does go some way towards describing the process by which food is propelled along the tract, through peristalsis (the sequential contraction of smooth muscles) and the variations in pressure caused by the movement of the diaphragm in breathing:

"When with the transverse muscles the superfluities of the intestine are squeezed out of the body, these muscles would not perform this function well nor with power unless the lung were filled with air. If the lung were not filled with air, it would not itself fill up the whole diaphragm; the diaphragm would remain relaxed, and the intestines pressed on by the transverse muscles would move towards the side which gives way to them, which would be the diaphragm. But if the lung should stay completely full of air and you do not exhale it, then the diaphragm will stay taut and hard and resist the ascent of the intestines compressed by the transverse muscles, whence of necessity the intestines will rid themselves through the rectum of a great part of the superfluities contained within them."

The drawing at lower center depicts the stomach, liver and spleen, with the splenic and superior mesenteric veins joining to form the hepatic portal vein. The short gastric veins drain from the left side of the stomach to the spleen, and what may be a gastroepiploic vein drains from the middle lower part of the stomach into the splenic vein.

Text from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomy, London 2012

Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Recto: Traces of black chalk, pen and ink. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink

Measurements

19.2 x 13.8 cm (sheet of paper)

Other number(s)

Alternative title(s)

Recto: The gastrointestinal tract, and the bladder. Verso: The gastrointestinal tract