-

1 of 253523 objects

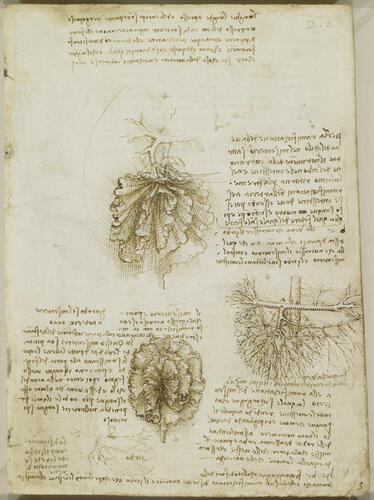

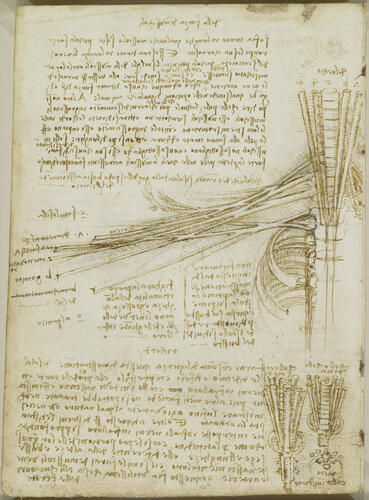

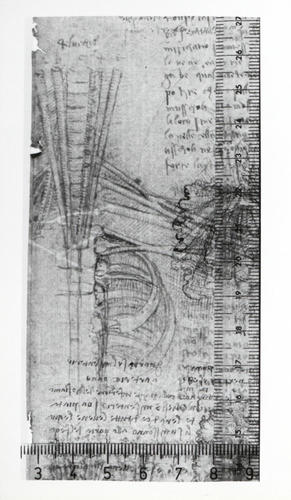

Recto: The mesentery of the bowel and its blood supply, with notes. Verso: The brachial plexus c. 1508

Pen and ink over black chalk | 19.3 x 14.3 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919020

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

Recto: The mesentery of the bowel and its blood supply, with notes. Verso: The brachial plexus c. 1508

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

Recto: The mesentery of the bowel and its blood supply, with notes. Verso: The brachial plexus c. 1508

-

A folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript B'.

On the recto: the portal veins, its tributaries and branches; two studies of the mesentery and the portal vein; the portal and gastric veins; with notes accompanying the drawings.

On the verso: the brachial plexus; diagrams of vessels, the trachea, and the oesophagus; with notes on the force of the muscles of the arms and legs, also on the structure of the neck. The principal drawing is labelled 'del vechio', ‘of the old man’, and is a fine example of the advances in Leonardo’s detailed anatomical knowledge resulting from the dissection of the centenarian described in RCIN 919027.

The brachial plexus is the network of nerves that runs from the spine to the arm. Its origin from five root nerves (ventral primary rami of cervical spinal nerves 5-8 and the first thoracic spinal nerve) is correctly shown, with the contribution of the first thoracic spinal nerve evident. These five roots unite to form three trunks – upper or superior, middle, and lower or inferior, just as Leonardo has pictured them. From that point their separation into anterior and posterior divisions, then cords and terminal branches becomes harder to follow in the drawing; some cutaneous nerves and terminal branches such as the median nerve and ulnar nerve can be discerned, but the untidiness and numerous crossings-out in Leonardo’s notes at centre left hint at his struggle to identify the destination of each nerve. The complexity of this area would have been compounded by the difficulty of working with unembalmed material – in this state the nerve trunks and their membranes are easily dissociated from one another and can be spread apart.

Leonardo has shown twelve stylised cervical vertebrae, rather than the correct seven, and the manner in which the spinal nerves issue from the vertebrae is very indistinct. Alongside the cervical vertebrae are vessels such as the internal jugular vein and common carotid artery, shown again in the subsidiary diagrams at lower right – two perspective views with the elements teased apart, and a cross-section. Along the right (proper) side of the thoracic vertebrae, and appearing to pass downwards from the spinal and intercostal nerves, are components of the sympathetic trunk and thoracic splanchnic nerves, which contribute to the innervation of the viscera. The long note above discusses the functioning of muscles in general. Below is a reminder to depict the systems of nerves, muscles, vessels and so on independently from each other, which ‘will be most useful to those who treat wounds’; and alongside the main drawing Leonardo writes ‘any one of the five branches saved from a sword-cut is enough for sensation in the arm’. This is an echo of one of the bases of anatomical knowledge in the millenia before Leonardo – his great predecessor Galen had derived much information from four years’ work as a gladiatorial physician in the second century AD.

Text from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; Probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Pen and ink over black chalk

Measurements

19.3 x 14.3 cm (sheet of paper)

Markings

watermark: Letter A, partial [MS B]

Other number(s)