-

1 of 253523 objects

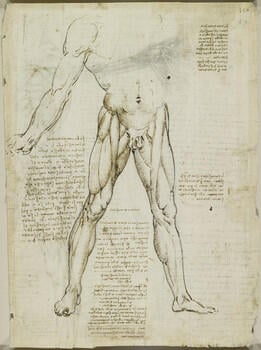

Recto: The muscles of the leg. Verso: The muscles of the trunk and leg c.1510-11

Recto: Pen and ink over black chalk. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink, wash | 28.6 x 20.7 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919014

-

A folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript A'.

Recto: a study of a man from the shoulder down, facing the spectator; with legs apart, showing the leg muscles, the shoulder and extended right arm (the left arm not shown); notes on the drawings.

The principal drawing is a hybrid of life study and dissection drawing, the figure posed with many of the external features apparent, but the muscles shown with a degree of differentiation that suggests a flayed figure. Leonardo labelled the muscles vastus lateralis (a) and tensor fasciae latae (b), and in the rather opaque note alongside he attempts to analyse their interrelationship. This is a complex region, as the fascia lata, the deep connective tissue of the thigh, is attached to many different structures, including both vastus lateralis and tensor fasciae latae. Leonardo had perceived that the two muscles were connected in some way, but he was unable to make full sense of his findings. His mistaken conclusion was apparently that the two muscles were attached to the femur and also, independently, to each other, such that if one were damaged the other would still be able to contribute to movement of the femur.The depiction of the long, thin sartorius muscle, passing obliquely across the front of the thigh, led Leonardo to comment on the shape of muscles in the note at centre right. He distinguished between two shapes (initially three, corrected to two) – the usual bulbous muscolo, whose name derives from its supposed resemblance to the shape of a mouse (Latin musculus, ‘little mouse’), and the longer, thinner lacerto (Latin lacertus, ‘lizard’). In fact Leonardo very rarely used the term lacerto in his notes, almost all muscles being called muscolo. The third shape that Leonardo considered was probably the pesce, with a double or bifurcated ‘fish-tail’ origin; he occasionally calls biceps brachii the ‘fish of the arm’, and on 19008r rectus femoris (and not biceps femoris) is the ‘fish of the thigh’.

At the top of the page is a faint drawing of the anterior aspect of the shoulder (with pectoralis major removed), very similar to that at lower left of 19003v but with more detail at the neck. Why Leonardo chose not to fix the outlines with ink is puzzling, and much of the fine detail has been lost by rubbing of the charcoal over the centuries. As the accompanying note explains, the muscles are ‘lean and thin’ so that the spaces make ‘windows’ on what lies beyond – the origin of Leonardo’s ‘thread diagrams’.

Verso: a man in profile to the right, from neck to ankle, showing the superficial muscles; a man's right leg, showing the superficial muscles of the thigh; numerous small studies, diagrams and notes on the drawings.

The page is dominated by a boldly modelled study of the superficial muscles from the neck to the ankle. Trapezius has been removed from the neck and shoulder, and thus the spine of the scapula is prominent. Latissimus dorsi occupies the region under the arm; to its right is serratus anterior, interdigitating on the lower ribs with the external abdominal oblique muscle, the lower portion of which descends to its insertion on the iliac crest of the pelvis. Below the iliac crest are the muscles tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius and maximus converging on the greater trochanter. Running down the side of the thigh from the greater trochanter is vastus lateralis; Leonardo distinguished an anterior portion of that muscle and stated that it is attached to the skin – as it appears to be continuous with tensor fasciae latae this may in fact be a portion of the fascia lata, the tissue that connects many of the structures of the thigh. To the left is a front view of the leg with muscles such as sartorius, tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius clearly shown.

The small diagrams and notes at upper centre constitute an astute analysis of the structure and function of muscles. In diagrammatic form Leonardo distinguishes between a broad, thin tendon of attachment, a muscle body and a narrower tendon of insertion, with connections to the nerves, arteries and veins. Each of these components is identified with a specific function – not just the mechanical function of the muscle and tendon, but also the sensation due to the nerve, and the traditional concepts of ‘nourishment’ provided by the venous system and ‘spirit’ by the arterial. In two further small diagrams Leonardo sketches a muscle cut through the middle to show that its section is not circular.

The two drawings at upper left represent intercostal or subcostal muscles (more likely the latter, as Leonardo counted only seven). The annotation ‘true position of the muscles’ by the left-hand diagram indicates Leonardo’s knowledge of the oblique positioning of these muscles with respect to the ribs – the diagram alongside, labelled ‘these muscles are poorly positioned’, shows the schematic muscles passing perpendicularly from rib to rib. The notes and diagram below outline a system by which the act of breathing aids propulsion of the intestinal contents. Leonardo states that when the subcostals shorten, the ribs are pulled together, the chest is compressed and thus the lungs are squeezed in exhalation. When the subcostal muscles relax, the ribs dilate, the lungs inflate, and the diaphragm, attached to the bottom of the ribs, stretches and flattens, thus compressing and propelling the contents of the colon. While much of this is incorrect, Leonardo did realise that the lungs themselves are passive and inflate due to expansion of the chest.

[Text from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012]

A partial copy of both recto and verso by Aurelio Luini (on a sheet with a partial copy of 919005v) was at Christie's, London, 2 July 2019, lot 42; with Stephen Ongpin Fine Art 2022 (cat. 7).Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Recto: Pen and ink over black chalk. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink, wash

Measurements

28.6 x 20.7 cm (sheet of paper)

Category

Object type(s)

Other number(s)