-

1 of 253523 objects

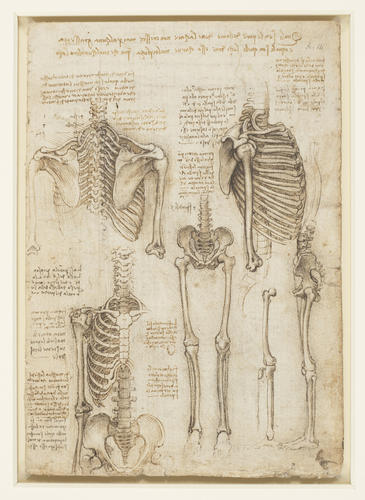

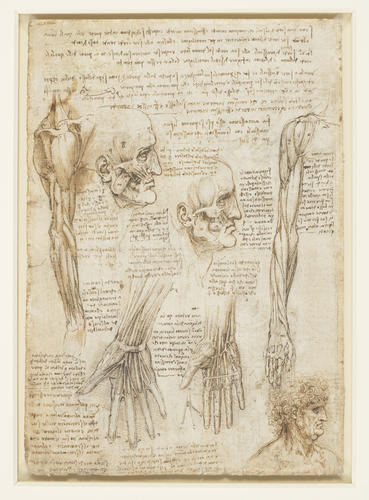

The skeleton (recto); The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand (verso) c.1510-11

Black chalk, pen and ink, wash | 28.8 x 20.0 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919012

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

The skeleton (recto); The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand (verso) c.1510-11

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

The skeleton (recto); The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand (verso) c.1510-11

-

A folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript A'.

Recto: the bones of the thorax, showing the spinal column and upper arm; the bones of a figure from the neck to the pelvis; the skeleton of the pelvis and the legs; the bones of a right leg; notes on the drawings.

This page constitutes the most complete representation of a skeleton in the whole of Leonardo’s surviving oeuvre. The vertebral curvature and oblique rib placement are well shown, and the drawing at lower right captures the correct tilt of the pelvic girdle, with a thread from the anterior surface of the ilium through the patella to the tibia illustrating the action of the quadriceps. That drawing is very similar to the equivalent study on RCIN 912625, but Leonardo has here corrected the length of the ischium.

Whether Leonardo had attempted to visualise a complete skeleton or had actually joined dried bones back together, some errors of detail were perhaps inevitable. The scapula is too long (it should extend from around rib 2 to rib 8); the humerus is well drawn throughout, but the trochlea – the depression in the middle of its lower end, for articulation with the ulna – is on the wrong side of the humerus. In the side view at upper right, the angle of descent of the first two ribs is too acute, the front-to-back dimension of the thorax is somewhat excessive, and the last two floating ribs are far too long.

In the drawing at lower left, the articulations of the clavicle and first rib with the manubrium (labelled m) appear accurate, and Leonardo correctly places the articulation of the second rib at the sternal angle, where the manubrium joins the body of the sternum. But he shows separate sternal segments, and an odd arrangement of the lower ribs, in particular their cartilaginous connection to the sternum. He also depicts the acromion (the process of the scapula at the furthest point of the shoulder) as a separate bone: that this was deliberate is confirmed in a note, ‘First depict the shoulder without the bone a, and then put it in’. In the young the acromion is connected to the body of the scapula by cartilage that later ossifies, and in some individuals it can remain separate, but elsewhere in the manuscript Leonardo plainly shows the acromion as a part of the scapula.

*

Verso: two studies of a head in profile to the right, showing facial muscles; a right arm and shoulder in profle to the right; a study of a right arm and hand seen from in front; two studies of a right hand, with the palm towards the spectator, showing arteries and nerves; the head of a man with curly hair, in profile to the right.

Leonardo fits a remarkable amount of information onto this page. There are three main subjects: the hand; the muscles of the shoulder and arm, essentially repeating the drawings on RCIN 919008v; and the muscles of the face, a subject treated nowhere else in Manuscript A.

The two studies of the hand are labelled 5th and 6th, and thus continue the sequence begun on 919009r. The drawing to the left depicts the entry of the median and ulnar nerves into the hand, with the correct distribution of the nerves for cutaneous sensation. The fibrous tendon sheaths are fully indicated, as is the transverse carpal ligament (it was represented by two threads on 919009r), with the median nerve and long flexors of the fingers passing through the carpal tunnel. In the drawing to the right the ulnar artery enters the palm and forms the superficial palmar arch, with the common palmar and proper palmar digital arteries distinct. Running across the palm is the superficial transverse metacarpal ligament (cf. its deep counterpart in the lower right drawing on 919009r).

The studies of the facial muscles are highly accurate. The drawing to the left depicts the superficial muscles, notoriously difficult to dissect as they may originate and/or insert into the deep surface of the skin. We see part of the complex of muscles that raise the upper lip, and Leonardo reminds himself to see if this is the same muscle structure that raises the nares (nostrils) of the horse, as studied on fig. 8. He attempted to identify the function of each muscle in the surrounding notes: ‘h is the muscle of anger; p is the muscle of sorrow; g is the muscle for biting; o t is the muscle of anger’. Leonardo also reminds himself to determine whether the nerves that cause movement in the face issue directly from the brain – he has comprehended the difference between spinal nerves and cranial nerves. In the second drawing some of the superficial facial muscles have been removed to reveal the deeper structures.

Text adapted from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Black chalk, pen and ink, wash

Measurements

28.8 x 20.0 cm (sheet of paper)

Category

Object type(s)

Other number(s)