-

1 of 253523 objects

The surface anatomy of the shoulder and arm (recto); The vertebral column (verso) c.1510-11

Recto: Black chalk, pen and ink. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink, wash | 28.6 x 20.0 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919007

-

A folio from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript A'.

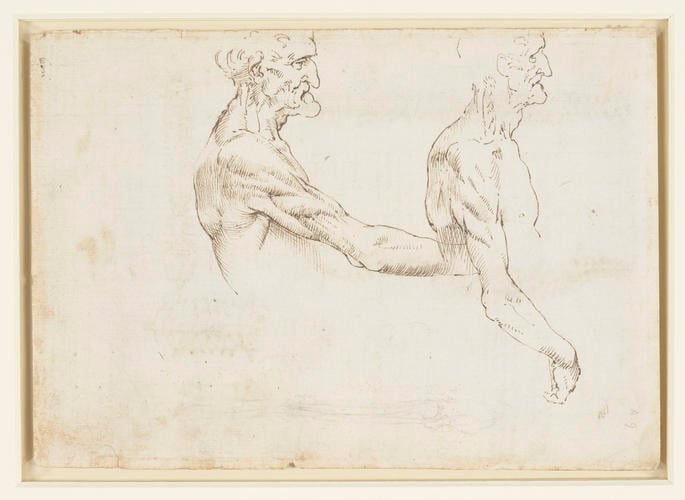

Recto: two half-length studies of an old man turned in profile to the right, one with the right arm raised, the other with the right arm lowered; showing the muscles of the thorax and the arm; the bones and muscles of a right upper limb.

*

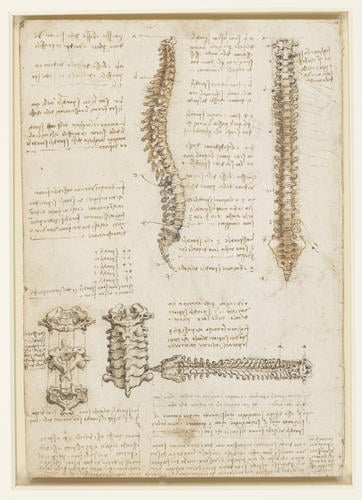

Verso: two studies of the spine; a horizontally placed study of the spine; two detailed studies of vertebrae on a larger scale; numerous notes on the drawings.

This is the first accurate depiction of the spine in history, and five hundred years later no artist or anatomical illustrator has surpassed Leonardo’s accomplishment. The drawing at upper left depicts an ergonomically correct spine with its curvatures and sacral tilt perfectly shown. The only error is that Leonardo has shown twelve thoracic vertebral bodies (correctly) but thirteen spines – between the second and third thoracic vertebrae is a spinous process with no vertebral body, but so convincing is Leonardo’s drawing that even most anatomists fail to notice this until it is pointed out.

To the right is a correctly articulated frontal view of the spine. The subtlety of Leonardo’s shading allows the curvatures to be clearly understood, and variations in the sizes of the vertebral bodies and transverse processes are carefully recorded – vertical lines either side of the spine give the maximum width of the processes. To the right of the image, long oblique lines indicate where the spinal nerves would be, including the brachial and sacrolumbar plexus. The viewpoint of the image at lower right is a little unusual, showing the posterior aspect but from an elevated position, and Leonardo’s reasons for choosing this aspect are not explained in the accompanying notes – perhaps he wished to give a sense of the length of the posterior spinous processes.

The note at centre left is deceptively simple in its accuracy. It enumerates the vertebrae in a completely modern manner, though Leonardo did not have the vocabulary that we use. Thus he counts seven cervical segments, twelve thoracic segments (he ignored his extra-spine mistake), five lumbar segments, five sacral segments and two coccygeal segments. Simply stating the correct number of fused sacral vertebrae would have secured Leonardo a place in anatomical history, but this last number requires comment. There is no correct number of separate segments to the coccyx – the ‘tail’ of the embryo develops and then degenerates, and the degree of degeneration accounts for variation between individuals in the number of segments. Modern textbooks state that it is composed of two to three or even three to five rudimentary segments; Leonardo saw two distinct segments in his subject, and we cannot say that he was wrong.

The drawing at lower left demonstrates how the first and second cervical vertebrae (atlas and axis) fit onto the third, using the diagrammatic convention of the ‘exploded view’. The major variations in the shape of each of these vertebrae clearly intrigued Leonardo. To the right he presents a detailed view of the cervical vertebrae assembled, with vertical lines again indicating that the transverse processes of the first and last are equal in width.

Text from M. Clayton and R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Recto: Black chalk, pen and ink. Verso: Black chalk, pen and ink, wash

Measurements

28.6 x 20.0 cm (sheet of paper)