-

1 of 253523 objects

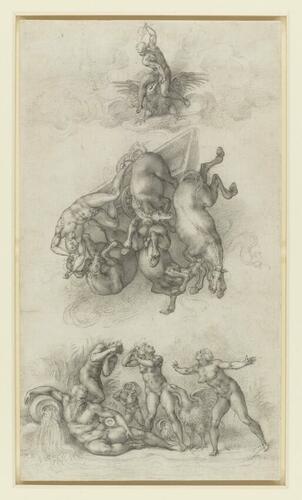

The Fall of Phaethon 1533

Black chalk; red chalk on the verso | 41.3 x 23.4 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 912766

-

A highly finished drawing of Phaethon, his chariot and four horses, tumbling from the sky, having been hit by a thunderbolt from Jupiter, seated above on an eagle. Below are three mourning women, a child and a swan, and a recumbent river god.

The story of Phaethon is told at length in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I, 750ff). Apollo, the sun god, offered his son Phaethon the granting of a wish, to prove that he was his father. Phaethon asked to drive the chariot of the sun for one day: Apollo begged him not to demand that, but the youth would not relent. He soon lost control of the chariot – the horses pulled it too high and the earth froze, then too low and the land was scorched and the oceans boiled. To save the earth, Jupiter struck Phaethon and his chariot from the heavens with a bolt of lightning.

Michelangelo presents the composition in three distinct groups. Above, a youthful, beardless Jupiter sits astride his eagle, twisting his body as he prepares to hurl his lightning bolt. At the centre, Phaethon, his chariot and his four contorted horses plummet to earth. Below, Phaethon’s three sisters, the Heliads, lament his fate; they were soon to be transformed into poplar trees, and alongside, a cousin, Cycnus, has already been turned into a swan. Reclining at the left is the god of the River Eridanus, into which Phaethon fell, with an attendant water-bearer.

Michelangelo made the drawing in Florence in the summer of 1533, as a gift for his young friend Tommaso de’ Cavalieri in Rome; it is one of four drawings described by the artist’s biographer Giorgio Vasari as having been executed for Cavalieri (Lives of the Artists, 1550 and 1568; see also RCIN 912771, 912777, 913036). Cavalieri acknowledged receipt of the drawing in a letter to the artist of 6 September 1533: ‘forse tre giorni fa io ebbe il mio Fetonte assai ben fatto; e allo visto il papa, il cardinal de Medici e ugnono’ (‘perhaps three days ago I received my Phaethon, very well done, and it was seen by the Pope, Cardinal [Ippolito] de’ Medici, and everyone’). This is the most highly finished of three variants of the composition drawn by Michelangelo, and probably the last (though there has been much discussion on this point); the other two, in the British Museum and the Accademia in Venice, each bear notes from the artist to Cavalieri asking for his approval of the composition.

The subject is a warning of the dangers of hubris, and in the context of Michelangelo’s relationship with Cavalieri, it can be read either as paternal advice to a young man starting his journey through life, or as a confession of Michelangelo’s feelings of unworthiness in his devotion – his letters and poems for Cavalieri speak of his presumptuousness in daring to love him. The tripartite, tiered arrangement on a strict vertical axis gives the composition an inexorable, pitiless quality and broadens its significance. It is organised in the same manner as the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, which Michelangelo was beginning to devise in the same year: a divine upper zone (and the pose of Jupiter is close to that of Christ in sketches towards the Last Judgement), an aerial middle zone and an earthbound lower zone. The drawing thus alludes not just to the particular circumstances of Michelangelo’s relationship with Cavalieri, but more generally to the terrors of fate and the irreversible consequences of our actions.

Like the Tityus and Ganymede, Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici commissioned (according to Vasari) an engraved crystal of the Phaethon from Giovanni Bernardi; the resulting crystal, now in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, omits the figure of Jupiter, and combines elements of the Windsor and British Museum drawings in its figuration. Bernardi then carved a second set of crystals of the three drawings, probably as a commission from Pier Luigi Farnese, to be set into a casket designed by Francesco Salviati alongside other crystals after Perino del Vaga; that casket is lost, but the designs of the crystals are known from metal plaquettes.

Nicolas Beatrizet reproduced the drawing in an engraving around 1550 (RCIN 830373-4), and that print was then the model for numerous copies (830375-8) and derivations in other media.

On the verso, in red chalk, is a drawing of a woman, her right hand to her plaited hair, a lightly sketched mirror in her left; she might be a personification of Truth, Prudence, the Active Life, or some such. Wilde (in Popham & Wilde 1949) associated the study it with the figure of Leah for the tomb of Julius II – a statue almost complete by 1542, but conceived earlier, and possibly one of the ‘new’ statues for the tomb for which Michelangelo wished to prepare full-sized clay models in 1532-33. But the evident weaknesses of the drawing have led some scholars to attribute the verso to a pupil of Michelangelo, such as Antonio Mini (1506-34/36; see eg. Joannides, Michelangelo and his Influence, 1996, no. 9b); if it is by Mini, it must have been executed before he left Florence for France in autumn 1531. Regardless of the authorship, the verso must presumably have been executed before the recto, and it seems extraordinary that Michelangelo should have laboured over a drawing of the perfection of Phaethon on a sheet of paper that had already been used.Provenance

Tommaso de' Cavalieri; Emilio de' Cavalieri, from 1587; Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, by 1602; listed in George III's 'Inventory A', c. 1800-20, p. 45, 'Mich: Angelo Buonaroti' / Tom. II (c. 1802): '7. 'Fall of Phaeton...[Black Chalk]'

-

Creator(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Black chalk; red chalk on the verso

Measurements

41.3 x 23.4 cm (sheet of paper)

Category

Object type(s)

Other number(s)

Alternative title(s)

Verso: a woman and a study of an ear