-

1 of 253523 objects

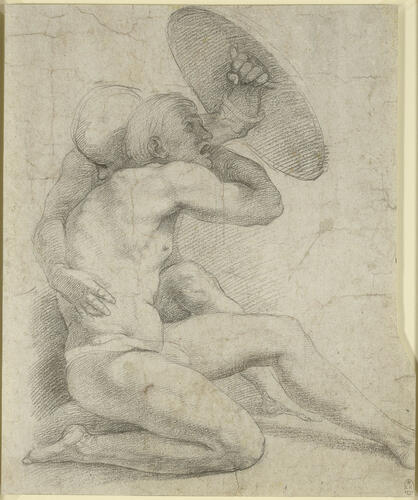

Two nude figures crouching c.1512

Black chalk. Watermark of a crossbow in a circle. | 26.6 x 22.4 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 912736

-

The drawing and RCIN 912735, along with several composition and figure drawings in other collections, are studies for an unexecuted Resurrection, possibly designed by Raphael for the Chigi chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Pace in Rome, but for which no document or other early reference is known. It is possible that Raphael also designed a complementary Resurrection for the Chigi chapel in another Roman church, Santa Maria del Popolo, the evidence for which is discussed below.

Three composition studies for the project are known. The earliest, a highly dynamic sketch at Oxford (Parker 559v), must have come at the very start of the design process, and concentrates on a group of soldiers at what must have been the lower right of the composition. The first sketch on the sheet comprises a soldier bracing himself against a flagstaff bent with the force of Christ's emergence; another soldier staggers away from the tomb, head down; a third is thrown backwards on the ground; and maybe one more is lost in a tangle of lines. The first two of these figures were then studied again immediately to the left, together with another soldier shielding his face; this soldier was then studied in nine further variants on the sheet (one in stylus alone). There are also sketches for, at lower left, a group of angels to flank the emerging Christ, and at centre a kneeling figure who found no further development.

The next drawing, at Bayonne (inv. 1707), is the only study of an entire composition, with an angel seated on the edge of an open sarcophagus gesturing upwards at the risen Christ. The lower right portion of the composition retains from the earlier study the staggering figure and the soldier falling backwards, and adds two soldiers at lower left raising their shields and a third seated cowering on the plinth of the sarcophagus.

In the final surviving compositional sketch, also at Oxford (Parker 558), the lower right of the composition is little changed from the Bayonne study, but the lower left is completely different. A soldier seated on a rock and seen from behind flings his right arm upwards in alarm; beyond him are two figures reprised from the earlier studies -- one crouching and shielding his face, another at top left, in beautiful contrapposto, apparently holding onto a standard.

Four of these figures were then studied from the life in a series of beautiful black chalk drawings. The staggering figure seen in RCIN 912735 had changed little since the start of the design process; the two figures in the present study, 912736, were developed from the single kneeling figure at the centre left of the Bayonne sketch; and at Oxford are studies for the seated figure seen from behind and for the sprawling soldier at lower right (Parker 559, 560).

In 1990 David Franklin published a fragment of a small Resurrection by Raffaellino del Colle that includes three of these four figures (excluding the staggering guard, 912735) arranged roughly as in the second Oxford sketch (‘Raffaellino del Colle’, Studi di Storia dell’Arte, 1990, pp. 145-59). The two soldiers in the foreground are also seen in Raffaellino's Resurrection altarpiece for the Duomo of Borgo Sansepolcro. Raffaellino was born c.1494-97 and probably arrived in Rome shortly after Raphael's death, becoming a pupil of Giulio Romano, one of Raphael's heirs, and he would have had access to many of Raphael's drawings. The fact that the soldiers in his paintings are in the same relationship to each other as in the Oxford sketch indicates that Raffaellino knew them as an ensemble, not as individual study sheets alone.

It would be reasonable to suppose that the Raffaellino fragment recorded to some degree the lower part of Raphael's final design for the Resurrection project, but for the existence of three further life studies of individual soldiers, none of whom is prefigured in the known compositional sketches. One, in the British Museum (1854,0513.11), shows a twisting seated figure holding his arms around his head, though he might be discernable in the densest part of the first Oxford sketch. Another, at Chatsworth (Jaffé 317), is of three figures sprawling to the left. Again, these studies were known beyond Raphael’s studio: the London figure (in the same sense) and two of the figures from the Chatsworth sheet (reversed) are found combined in an engraving of vintagers by the Master HFE (Bartsch XV, p.464, no. 5).

Finally, at Besançon (inv. 2301) and Frankfurt (inv. 381v) are two versions of a seventh study, a variant on 912735, with the figure turned a little to the left, stooping less and raising his right hand further to clutch his head. Both were routinely dismissed as copies before Gere and Turner (Drawings by Raphael, 1983, nos. 168ff) raised the possibility that one or both might be originals; their attribution is unimportant here, for even if both are copies they still demonstrate that Raphael did study a figure in this pose.

The existence of such a number of developed figure studies is problematic, for it is impossible to see how Raphael could have fitted all ten figures (and there may well have been still more figure studies, now lost) into a single composition without it becoming overcrowded – the second Oxford sketch and the Raffaellino fragment have a fully satisfactory complement of figures. Further, the head and shoulders of the figure at the left of the Chatsworth drawing repeat those of the Oxford seated soldier seen from behind; and the Besançon/Frankfurt figure is essentially the same as 912735, seen from a different angle. Raphael would never have allowed such repetition in a single composition.

There are two plausible alternatives to explain this plethora of figure studies. Either Raphael resolved the composition to a degree that warranted individual figure studies, but then scrapped and redesigned the lower part of the composition; or he designed more than one composition of the Resurrection, one with the Windsor and Oxford figures (as recorded in part by the Raffaellino del Colle fragment), another possibly including the London, Chatsworth and Besançon figures. (Beyond the Bayonne sketch we have no indication of the upper portion of the Resurrection.) The first option would be out of character, for among all of Raphael's executed projects there is no example of a figure studied from the life with such care who was then left out of the final composition. The evidence for the second will now be examined.

In an article of 1961, Michael Hirst (‘The Chigi Chapel in S. Maria della Pace’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, pp. 161-85), contended that the intended destination of Raphael's Resurrection was the Chigi chapel in Santa Maria della Pace, Rome. The external nave wall of that chapel is frescoed with Sibyls by Raphael, and Prophets probably by Timoteo Viti to Raphael's design, executed probably in 1511-12. Those sibyls and prophets bear tablets and scrolls with inscriptions alluding to the Resurrection, which suggests an intended altarpiece of that subject. There is a documentary reference of 1521 to a gilded frame ‘per la tavola daltar che andava alla pace’ (‘for the altarpiece which went in the Pace’), made to Agostino Chigi's orders and thus ordered during Raphael's lifetime (Raphael died on 6 April 1520, Chigi just four days later).

In December 1520, Leonardo Sellaio reported in a letter to Michelangelo that Sebastiano del Piombo would set to work on ‘la tavola alla Pace sotto le fighure di Raffaello’ (‘the panel in the Pace below Raphael’s figures’), but apparently nothing was done during the 1520s. Ten years later, on 1 August 1530, Sebastiano signed a contract with Agostino's heirs to paint two altarpieces, for the Chigi chapels of both Santa Maria del Popolo and Santa Maria della Pace; the subject of the Pace altarpiece was to be the Resurrection. All this evidence supports the contention that Raphael designed an altarpiece of the Resurrection for the Chigi chapel of the Pace around 1512, that he painted nothing, and that the commission was given to Sebastiano after Raphael's death. (Sebastiano in turn failed to discharge his obligations, and the chapel now houses a sculptural assemblage of the seventeenth century.)

Objections to the idea that all Raphael's Resurrection drawings were for an altarpiece for the Pace centre around the size of a painting necessary to incorporate all those figures, without them being demeaningly small. Cecil Gould (‘Raphael at S. Maria della Pace’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1992, pp. 78-88) pointed out that the available space for an altarpiece in the Chigi chapel of the Pace was only about 150 x 125cm, and suggested instead that the altarpiece was to be a two-figure group of the Pietà. Gould proposed instead that the intended site of the Raphael's Resurrection was Agostino Chigi’s other chapel, in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, where the space for the altarpiece is much larger.

The Chigi chapel in the Popolo was intended to be the burial place of Agostino Chigi. Building work began to Raphael's designs probably in 1512-13 and was completed in 1516. The figural elements from Raphael’s original scheme comprise two marble sculptures of the prophets Jonah (see RCIN 990804) and Elijah in niches, and a bronze relief of Christ and the Adulterous Woman, initially in the base of Agostino's pyramidal wall-tomb and now installed as the altar frontal, all by the sculptor Lorenzetto; and mosaics of God the Father creating the celestial universe in the cupola. The mosaics in their entirety, and the sculptures to varying degrees, depend on designs by Raphael.

The extant altarpiece is a Birth of the Virgin by Sebastiano del Piombo. The 1530 contract for this between Sebastiano and Agostino's heirs, mentioned above, refers to an earlier (now lost) contract of 12 March 1526 for the altarpiece. Although there is no mention in the 1530 document of a change of subject, Shearman proposed that a carefully finished drawing by Sebastiano of the Assumption of the Virgin (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) was his 1526 design for the altarpiece, and that two otherwise contextless drawings by Raphael of the Assumption were in turn his studies for the originally planned altarpiece of the chapel (J. Shearman, ‘The Chigi Chapel in S. Maria del Popolo’, JWCI, 1961, pp. 129-60, for a full account of the Popolo project).

An altarpiece of the Assumption would indeed accord better with the design and iconography of the Popolo chapel than does Sebastiano's Birth of the Virgin. However the subject of the Resurrection would be still more appropriate for the chapel than would the Assumption, for this was to be the burial chapel of Agostino and his heirs. The prophets Jonah and Elijah can both be seen as antetypes of Christ – Jonah of Christ of the Resurrection, and Elijah of Christ of the Ascension – and together, it is that association that any contemporary viewer would have made.

On iconographic grounds, therefore, the Resurrection would have been the most appropriate subject for the altarpieces of the Chigi chapels in both the Pace and the Popolo. A possible scenario is therefore as follows. Around 1511-12, Raphael frescoed the façade of the Chigi chapel in Santa Maria della Pace and designed a Resurrection for its altarpiece, for which RCIN 912735 and 912736 were studies. But before he began to paint that altarpiece, Chigi switched Raphael's attentions to his other, mortuary, chapel in the Popolo, requiring designs for the architecture and figuration, including another altarpiece. Raphael therefore planned a second Resurrection, still with the intention of painting the Pace altarpiece and therefore not reusing the figures designed for the Pace. Due to Raphael’s many other commitments that painting was not begun either. But there is little direct documentary evidence to explain Raphael’s many studies for one or more paintings of the Resurrection, and this reconstruction must remain a hypothesis.

There exists, in fact, another Resurrection commissioned by Agostino Chigi (according to a biography written by a descendant, Fabio Chigi, a century after Agostino's death) – that by Girolamo Genga in the church of Santa Caterina da Siena in Rome. In 1519 the Sienese community in Rome (of which Agostino Chigi was a prominent member) founded a congregation dedicated to their patron saint, Catherine of Siena, based in the church of San Nicolò in the Via Giulia. In 1526 the congregation obtained the title to that church, tore it down and began building the present church of Santa Caterina. But Genga had left Rome in 1522 to enter the service of Francesco Maria della Rovere in Urbino, and it is therefore possible that his Resurrection was in fact painted for Santa Maria del Popolo. In August 1519, a draft of Chigi's will charged Raphael and the metalworker Antonio da Sanmarino with responsibility for overseeing the completion of the chapel in the Popolo (though no altarpiece was mentioned). Raphael and Genga were compatriots, both from Urbino, and had worked together briefly in their early years; Genga’s Resurrection is large enough for the Chigi chapel, and it is therefore possible that it was painted for the Popolo, before being transferred to Santa Caterina, at which point the Chigi family commissioned Sebastiano to execute a replacement for the Popolo. Against this scenario is the nature of Raphael’s figure studies for his putative ‘Popolo Resurrection’: these would suggest that Raphael had fully worked out a composition, and if Genga was subcontracted to paint the altarpiece, he would presumably have been expected by Chigi to have followed Raphael’s composition, rather than devising a new composition.

Text adapted from M. Clayton, Raphael and his Circle, 1999, nos. 21-22.Provenance

First recorded in the collection of George III, c.1810 (Inv. A, p. 51, no. 32)

-

Creator(s)

(artist) -

Medium and techniques

Black chalk. Watermark of a crossbow in a circle.

Measurements

26.6 x 22.4 cm (sheet of paper)

Markings

watermark: crossbow in circle [verso]