-

1 of 253523 objects

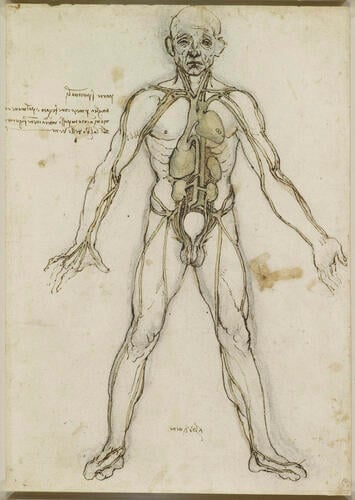

The major organs and vessels c.1485-90

Black chalk or charcoal, pen and ink, brown and green wash | 27.8 x 19.7 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 912597

-

An anatomical study of a standing man, legs apart and arms down, showing the major organs and vessels.

The drawing summarises Leonardo’s early understanding of the layout of the major organs and vessels, before he had carried out any significant human dissection. It is an amalgam of two medieval traditions: the ‘situs figure’ showing the position of the major organs within the trunk, and the ‘bloodletting figure’ showing the recommended sites for venesection and, occasionally, the paths of the superficial vessels.

Though the colour difference is now hard to distinguish, Leonardo used a brown wash for the venous system and a greenish wash for the arterial system – the contrast is most evident in the inferior vena cava and aorta. Though the origin of the vena cava from the liver is simply wrong, the relationship of the vena cava to the aorta and their bifurcations are essentially correct, and the right testicular artery and vein are present. The superior vena cava is shown splitting into the brachiocephalic veins and thence into the subclavian and internal jugular veins; the aortic arch is also drawn as a symmetrical structure, as in cattle but not in humans. The great saphenous vein can be followed from its origin on the upper side of the foot, running up the inside of the calf and knee and across the thigh. In the left arm, the cephalic vein (on the thumb side of the limb) is shown as part of the venous system, but the vessel on the little finger side of the limb, which should be the basilic vein, leads to an artery. The great saphenous, cephalic and basilic veins are among those most easily visible in a living subject, and were those most used in Leonardo’s day for bloodletting.

Since ancient times the heart had been acknowledged as of primary importance in the body. Aristotle wrote of it not only as the centre of life and heat, but also of intelligence and the emotions. In the second century AD Galen refined these theories: observation of vessels travelling from the intestines to the liver supported the notion that the liver was the source of nutrition or ‘natural spirit’, creating blood that was distributed by the veins to nourish the body and, in doing so, was consumed. There was no notion of circulation or return of the blood. A portion of the blood was thought pass from the right ventricle of the heart through the interventricular septum into the left ventricle, thus acquiring ‘vital spirit’, the ‘life force’, which was distributed through the body by the arterial system. The lungs existed to cool the heart. Variations on these basic ideas were espoused by the medieval followers of Aristotle and Galen, both Arab and European, and Leonardo’s drawing embodies these principles.

Text adapted from M. Clayton & R. Philo, Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist, London 2012, no. 1Provenance

Bequeathed to Francesco Melzi; from whose heirs purchased by Pompeo Leoni, c.1582-90; Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, by 1630; probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690

-

Creator(s)

Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Black chalk or charcoal, pen and ink, brown and green wash

Measurements

27.8 x 19.7 cm (sheet of paper)

Other number(s)