-

1 of 253523 objects

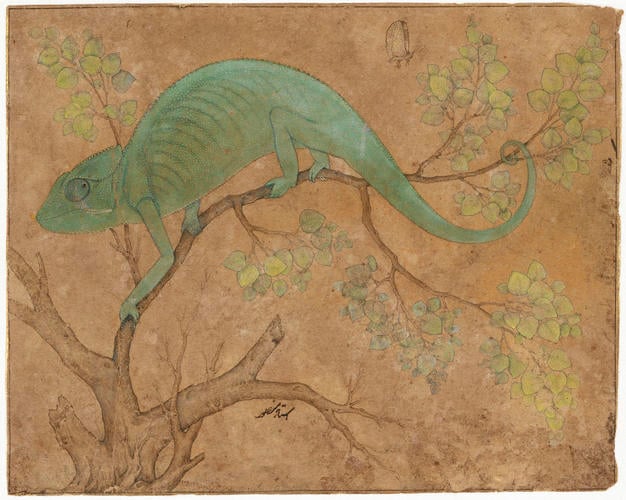

A chameleon 1612

Brush and ink with green bodycolour on discoloured paper | 11.0 x 13.8 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 912081

-

A drawing of a chameleon on a branch, facing profile to left, with its eye swivelled back; the end of its tail is curled round a branch, and a pale stripe is at the corner of its mouth.

Ustad Mansur was the leading animal painter at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (reg.1605-27), who bestowed upon him the honorific Nadir al-Asr, ‘Wonder of the Age’. Jahangir was a great patron of miniature painting, taking artists on his travels and priding himself on his attributional skills. He was also fascinated by the exotic, and commissioned his servant Muqarrab Khan to buy rarities from the Portuguese, who had established a colony in Goa on the west coast of India in the early sixteenth century. In 1612 a consignment of animals and birds arrived at Jahangir’s court from Goa, and he ordered his artists to include ‘portraits’ of these beasts in his illuminated biography.

This chameleon may have been one of the animals acquired in 1612. It has been identified as the flap-necked chameleon (Chamaeleo dilepis), a (usually) bright green species widely distributed throughout east Africa, and could have been bought as a curious pet by Portuguese traders on their voyages to India around the African coast. But the drawing does not show the occipital lobes as the back of its head, and is thus more likely Chamaelo zeylanicus, a closely related species distributed in India (information kindly supplied by Charles Klaver, 2011).

Mansur’s miniature is a scientifically precise depiction: he accurately recorded the pale stripe at the corner of the mouth, the line of white scales running along the underside of the body, and the unusual digitation of the chameleon - on each foot the digits are fused into two opposed ‘bundles’, two outer digits opposed to three inner on the forelimb, and vice versa on the hindlimb.

Over the next two centuries Mansur’s works were often copied by other artists and inscribed with his name, at first simply crediting him with the invention but in later years in an attempt to deceive, especially in works intended for the well-developed European export market. The attribution of a miniature such as this, inscribed with Mansur’s name below the branch, can thus be determined only through an assessment of quality. While the calligraphic branches and the discrepancies of scale are conventional and rather old-fashioned in their reminiscences of earlier Persian manuscripts, the chameleon itself is wonderfully tense and vital, and even a little comical, clinging to the thin branch and glancing slyly backwards at a tiny butterfly. The texture and lustre of its conical scales is mimicked by the painstaking application of hundreds of tiny discrete dots of green bodycolour, which stand proud of the surface of the paper. Such skill and sensitivity seem worthy of Mansur himself.

The provenance of the miniature is unknown, but the uneven discolouration of the paper suggests that it has been exposed to light for long periods. It is probably no more than coincidence that ‘A Book with some Indian Pictures’ in the Kensington list was ‘deliver’d for her Majtys [Queen Caroline’s] use [probably to be framed] in ye year 1728’.

Inscribed in Persian Ustad Mansur.

Text adapted from Holbein to Hockney: Drawings from the Royal Collection -

Creator(s)

(artist)(artist)(nationality) -

Medium and techniques

Brush and ink with green bodycolour on discoloured paper

Measurements

11.0 x 13.8 cm (sheet of paper)

Other number(s)

RL 12081Alternative title(s)

Chameleon