-

1 of 253523 objects

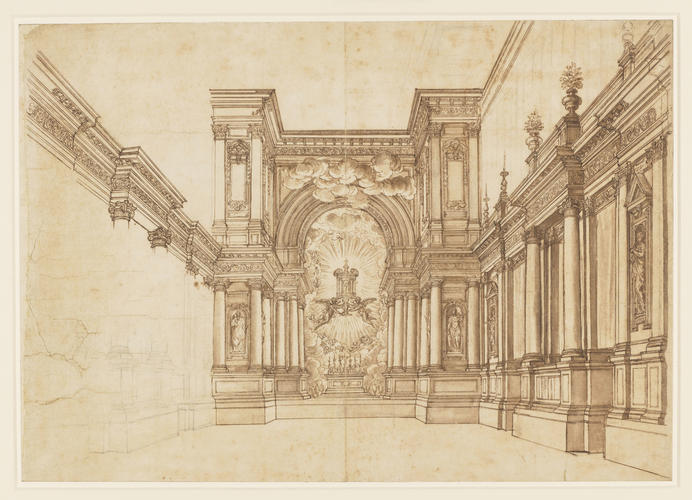

A design for a Quarantore c.1632-3

Pen and ink with wash over black chalk | 39.8 x 56.8 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 904448

Pietro da Cortona (Cortona 1596-Rome 1669)

A design for a Quarantore c.1632-3

-

In 1633 Pietro da Cortona was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Barberini to construct an elaborate temporary setting in San Lorenzo in Damaso, Rome, for the Quarantore celebrations - forty hours of continuous devotion of the consecrated host. The decorations were constructed of quickly worked materials, with wooden architecture, sculptures in papier mache or stucco, and paintings in watercolours on thin canvas or linen. Nonetheless this was the most costly such apparatus ever built, and was used annually for the next fifteen years.

This design is for the decorations for the Quarantore celebrated in February 1633 in the church of San Lorenzo in Damaso, Rome. The Quarantore, or Forty Hours’ Devotion, originated in the medieval tradition of placing the consecrated host in a symbolic tomb (the Easter Sepulchre) between Good Friday and Easter Sunday, forty hours being the time spent by Christ in the tomb. In the sixteenth century, beginning in Milan, this was transformed into successive periods of forty hours’ continuous prayer, passing from church to church and so establishing a perpetual devotion within the city. The altar was often decorated with a temporary structure or apparato to focus attention on the (physically small) host.

From the end of the sixteenth century it became usual in Rome to hold the Quarantore for nine days during February, successively in the churches of the Congregazione della Comunione Generale, San Lorenzo in Damaso and the Gesù, to divert the populace from the debaucheries of the carnival. San Lorenzo in Damaso was the titular church of the Vice-Chancellor, attached to his residence, the Cancelleria; and when Francesco Barberini was appointed Vice-Chancellor in November 1632 on the death of Ludovico Ludovisi (nephew of the previous pope, Gregory XV), he immediately aimed to outdo Ludovisi’s highly praised Quarantore of 1631. Barberini commissioned Pietro da Cortona to transform the interior of the church, obscuring its permanent architecture to create an all-enveloping setting for the meditation on the host.

The decorations were described in a contemporary account:

’On Thursday morning, in the church of San Lorenzo in Damaso, the oration of the Quarantore was celebrated, with an apparato that the most eminent Cardinal Barberini (Vice Chancellor and new titular of that church) had had most superbly made, in the form of a theatre with columns, niches, and gilded statues of saints with other ornaments; representing (on the high altar) the rays of the sun, in the middle of which was placed the Holy Sacrament supported by two huge angels, with a great quantity of candles in silver candlesticks on the said apparato, and with silver candelabra and continuous sermons and music, etc.’

This drawing shows the view down the length of the church. A screen closed off the side aisles and reduced the form of the church to an oratory. At the mid-point of the nave, pedestals supported free columns, flanked by niches containing the statues of saints, above which ran an entablature and an attic storey with candelabra and vases. The form of the clerestory is barely indicated, but seems to consist of low pilasters. The altar was surrounded by clustered columns supporting a triumphal arch, in front of which hung painted clouds. At the centre of the arch was the host itself, displayed in a monstrance supported by airborne angels, set against a backdrop of a sunburst with cherubs and clouds. The apparato was equipped with only a few visible candles (limited in number by an encyclical of 1592 that attempted to restrict the extravagance of the event), but was illuminated by countless other candles and lamps hidden by the architectural elements.

Nothing survives of the many ephemeral apparati that were such a feature of ceremonial in seventeenth-century Rome; they are known only through descriptions, drawings such as this, and engravings that were made to record them. Such apparati were little different in concept from stage scenery. Cortona had already designed the stage set for the first performance, in Palazzo Barberini in 1632, of the opera Sant’Alessio (the libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi, the future Clement IX, and the music by Stefano Landi, who also composed the music for the 1633 Quarantore). He received the commission to design the apparato for San Lorenzo in Damaso in December 1632, giving him less than two months to design and supervise its construction. The little time available, and the fact that the whole structure was intended to be temporary, meant that the decorations were constructed of inexpensive and quickly worked materials - the architecture of wood (painted in imitation of marble), the sculpture of papier mâché or stucco (again painted or gilded), the paintings in quick-drying tempera on thin canvas or linen. Nonetheless, this was to be the most costly Quarantore apparato ever built, and Cortona’s design was so successful that it was used for the celebrations in San Lorenzo each year for the next fifteen years.

Catalogue entry adapted from The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection: Renaissance and Baroque, London, 2007Provenance

Probably acquired by George III in 1762 as part of the collection of Cardinal Alessandro Albani; first recorded in a Royal Collection inventory of c. 1800-1820 (Inv. A, p. 112: Tom. II, 'Ornaments for insides of Churches, Pallaces, and other devices')

-

Medium and techniques

Pen and ink with wash over black chalk

Measurements

39.8 x 56.8 cm (sheet of paper)

Object type(s)