-

1 of 253523 objects

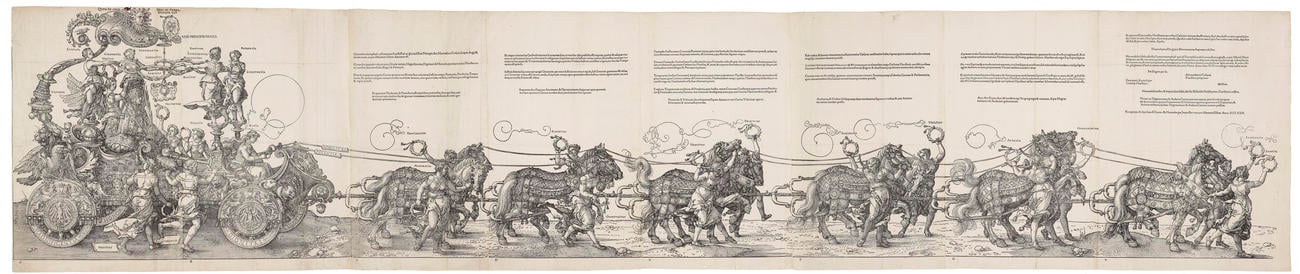

The Triumphal Cart of the Emperor Maximilian 1522 first Latin edition, published 1523

Woodcut from eight blocks | 47.9 x 230.0 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 830118

-

A woodcut showing the Emperor Maximilian in a triumphal chariot.

This large woodcut, over 2 metres in length, was originally planned as part of a huge printed frieze. The work, undertaken by a team of designers and woodblock cutters, was to show a triumphal procession celebrating Maximilian I, who had been Holy Roman Emperor since 1493. Dürer and his friend, the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, however, proposed a revised version of the chariot to Maximilian in 1518, and issued it as a posthumous memorial in 1522 (Maximilian died in 1519). This impression is from the first Latin edition, published in 1523.

The triumphal procession was one of a series of printmaking projects initiated by Maximilian in promotion of his person and his rule. These included a series of illustrated books, among them the Theuerdank, and a series of huge prints of which a great Arch of Honour and parts of the Triumphal Procession were published. These prints depict, on paper, the triumphal entries used by rulers to emphasise their power, which often involved the building of elaborate floats and carts, and temporary arches through which the processions could pass.

Dürer’s triumphal chariot shows the Emperor seated in a cart drawn by six teams of horses. The Emperor holds a palm, and a laurel wreath is being placed on his head by Victory, while other virtues holding laurel wreaths stand on the cart or lead the horses. The cart is driven by ratio (‘reason’) and the horses are reined with nobilitas (‘nobility’) and potentia (‘power’). The wheels of the cart, which are adorned with Maximilian’s symbols, the splayed eagle and the Burgundian flints, are named 'magnificentia', 'dignitas', 'gloria' and 'honor'. An extensive interpretive text, by Willibald Pirckheimer, is included on the print. Pirckheimer was largely responsible for the iconography of the chariot, over which he had corresponded with Maximilian in 1518. Drawing on a long tradition of triumphal entries, thought to date back to Roman emperors, the design implied a parallel between Julius Caesar, the archetypal Roman emperor, and Maximilian, the modern Caesar.

As Maximilian’s Triumphal Procession was not completed during his lifetime, we have no information about its intended distribution. Its planned size may indicate that it was intended for public rather than private display, and was to be sent to individuals or corporations in promotion of Maximilian’s rule. If, as seems likely, it was intended for display in such communal spaces, Maximilian’s Triumphal Procession should be seen in the context of the decoration of civic spaces with moralising scenes, historical victories and depictions of individual rulers’ might. This tradition can be traced back to the Middle Ages, but was given new potential by Maximilian’s employment of the reproductive print: images could be sent to many locations rather than being specific to one.

Dürer’s eventual issuing of the Triumphal Cart as a separate print after Maximilian’s death, however, had a slightly different emphasis. While the print still served to glorify the Emperor - if posthumously - Dürer’s prime intention was financial profit, as his annual salary, paid on the Emperor’s instructions by the city of Nuremberg, had ended with the death of Maximilian. In 1520, a year after the Emperor’s death and two years before the independent issue of this print, Dürer wrote to Georg Spalatin, chaplain of the Elector of Saxony, complaining that ‘the Council will no longer pay me the 100 florins, which I was to have received every year of my life from the town taxes and which was yearly paid to me during his Majesty’s life-time. So I am to be deprived of it in my old age and to see the long time, trouble and labour all lost which I spent for his Imperial Majesty. As I am losing my sight and freedom of hand my affairs do not look well.’

A bound set of Dürer's Apocalypse woodcuts was at Kensington by 1728, and in 1762 George III acquired an album of his prints with the collection of Consul Joseph Smith. Individual acquisitions to fill the gaps in the collection in the nineteenth century resulted in a fine group of Dürer prints at Windsor, often in excellent condition.

Catalogue entry adapted from The Northern Renaissance. Dürer to Holbein, London 2011Provenance

In the Royal Collection by c.1900

-

Creator(s)

(designer) -

Medium and techniques

Woodcut from eight blocks

Measurements

47.9 x 230.0 cm (sheet of paper)

Category

Object type(s)