-

1 of 253523 objects

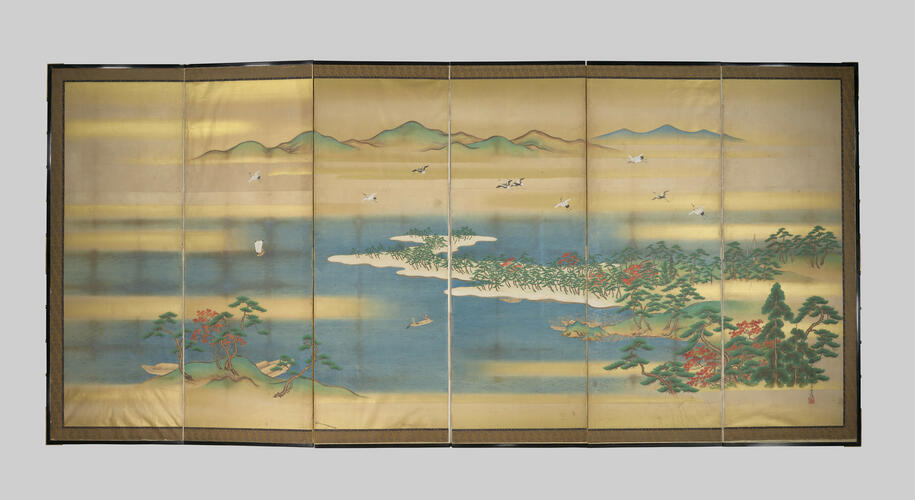

Six-panel folding screen painting 1860

Ink, colour and gold on paper, with mount of silk brocade, ebonised wood and brass | 176.0 x 256.8 x 11.5 cm (whole object) | RCIN 33544

-

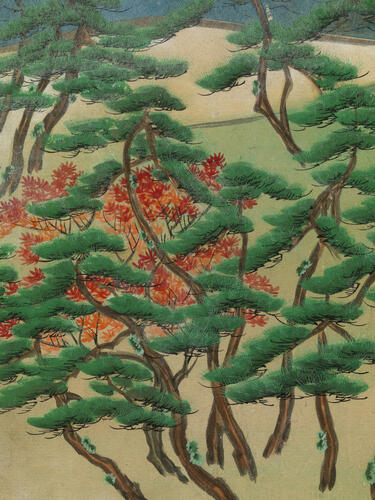

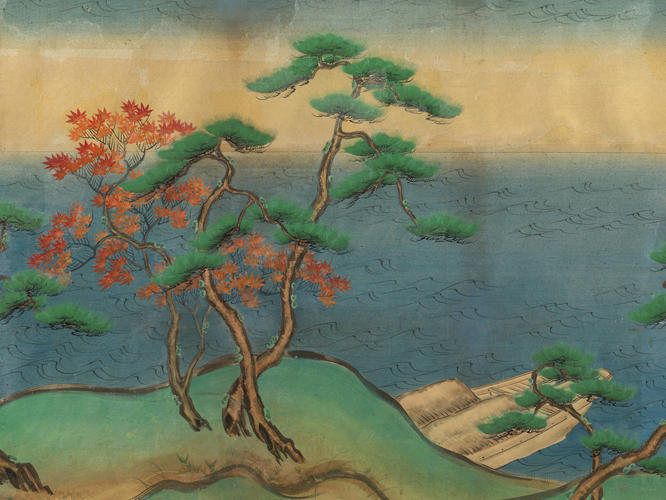

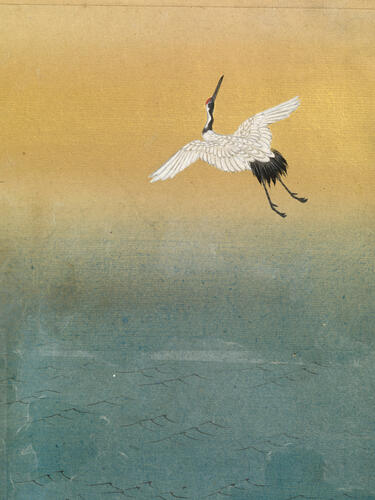

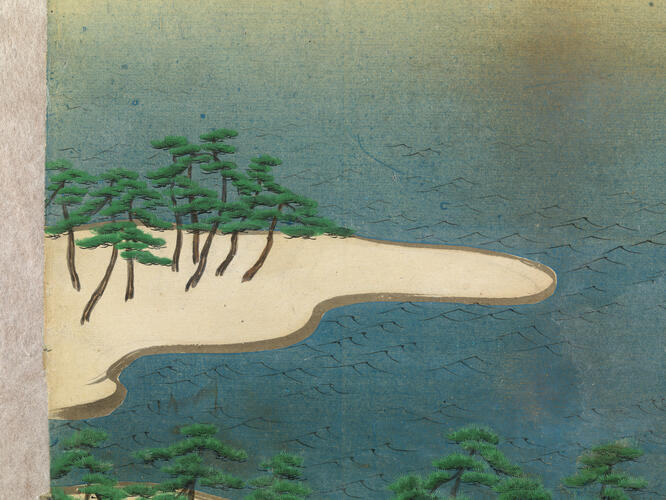

Nineteenth-century Japanese folding screen paintings (byōbu), each comprising several panels, were of a type and size usually intended for diplomatic gifts, continuing the tradition established in the sixteenth century. Screens were designed to be shown open, and the papered hinges and lightweight yet strong wooden core eliminated the need for intrusive frames separating the panels, thereby allowing horizontal orientation of a continuous image. This screen, along with RCIN 33530, were intended to be viewed together, show the changing seasons. RCIN 33530 depicts Mount Fuji in the spring, with pine trees and cherry blossom in the foreground, which includes figures. It is painted from a high viewpoint looking across the Fuji Five Lake region (Fujigoko) at the northern base of the mountain. This screen is dominated by Miho-no-Matsubara, a spit of land covered by pine trees, the foreground filled with pine and maple trees in rich autumnal tones beneath cranes in flight.

The screens were almost certainly a late Tokugawa-period diplomatic gift, given their similarity – in style, subject matter and imagery – to examples sent to Dutch monarchs. In 1845, one pair was sent to King Willem II (1792–1849) in acknowledgement of his advice, delivered via Philipp von Siebold, former physician at the VOC factory at Deshima, that Japan should voluntarily open itself to foreign trade to pre-empt the use of force by western nations. In 1856, ten pairs of screens were presented to King Willem III (1817–90) by Tokugawa Ieyoshi (1792–1858) as part of a larger gift in thanks for a steamship sent by the Dutch Government.

Following the signing of an Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1858, Tokugawa Iemochi likewise sent Queen Victoria eight pairs of gold-leaf screen paintings as part of a lavish gift in 1860. Although ‘10 sets of gilded Bioboe [byōbu]’ were originally intended for presentation, two pairs – including a scene entitled ‘Playing in the Snow’ from the Tale of Genji, Japan’s most celebrated work of literature – were removed as they were considered unintelligible to foreigners.

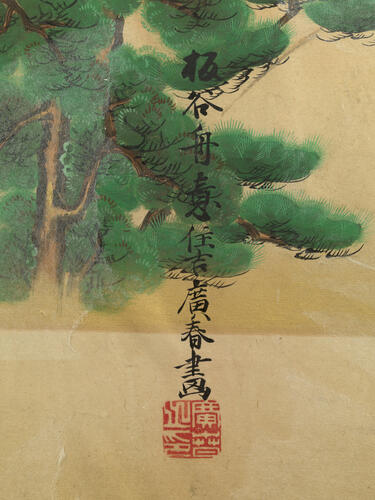

The screen paintings for Queen Victoria were to be designed by various artists, including Itaya Keishū Hironobu (1820–59), who had been among those responsible for the gifts sent to King Willem II, but he died and the work was passed to Kanō Shōgyoku Akinobu (1840–91). This pair were signed by the artist Itaya Hiroharu, who was the sixth-generation head of the Itaya lineage. Itaya Hiroharu does not appear in the Japanese records of the commission for Queen Victoria, but the use of his art name ‘Shū-i’ securely dates their production to the first half of 1860, since he changed his art name to ‘Kei-i’ in June that year. Itaya Hiroharu had been a pupil of the late Itaya Hironobu, so it is likely that he was invited to join the commission. These screens must therefore surely have formed part of the gift.

What makes these objects of particular interest is that they indicate the image the Japanese wanted to project in a new era of commercial and diplomatic engagement.

Text adapted from Japan: Courts and Culture (2020)Provenance

Probably sent to Queen Victoria by Tokugawa Iemochi of Japan in 1860.

Probably one pair (with RCIN 33530) of the '10 sets of gilded Bioboe (screens)' described in a translated list of gifts seen by Sir Rutherford Alcock, the British Consul General in Japan, on 14 July 1859 and received in England in 1860 (TNA FO 46/3: General Correspondence before 1906, Japan 1859, Jan.-Sept. 7).

The screens sent to Queen Victoria as diplomatic gifts would likely have been six-panel folding screens paintings, like these, and similar to those given to William II of the Netherlands in 1845. The attribution of this screen to Sumiyoshi Hiroharu securely dates its production to before 1860, since the artist changed his name. Thus although Sumiyoshi Hiroharu does not appear in the Japanese records of the 1859 commission for Queen Victoria, this screen and RCIN 33530 must surely have formed part of it. (These details have kindly been provided by Dr Rosina Buckland, Senior Curator East and Central Asia, National Musuem of Scotland). -

Creator(s)

(nationality)Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Ink, colour and gold on paper, with mount of silk brocade, ebonised wood and brass

Measurements

176.0 x 256.8 x 11.5 cm (whole object)