-

1 of 253523 objects

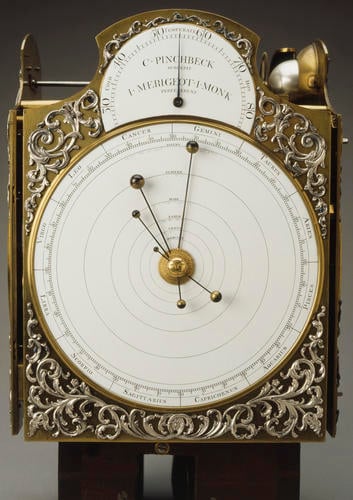

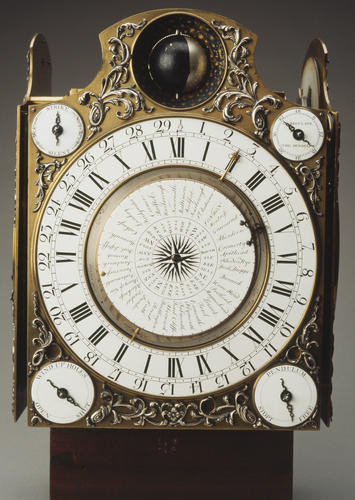

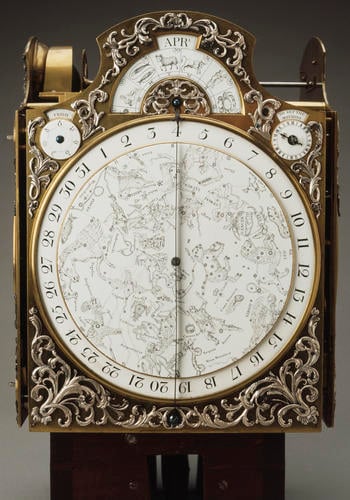

Astronomical clock 1768

Tortoiseshell, oak, gilt bronze, silver, brass, steel and enamel | RCIN 2821

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

Christopher Pinchbeck II (1710-83)

Table clock 1768

-

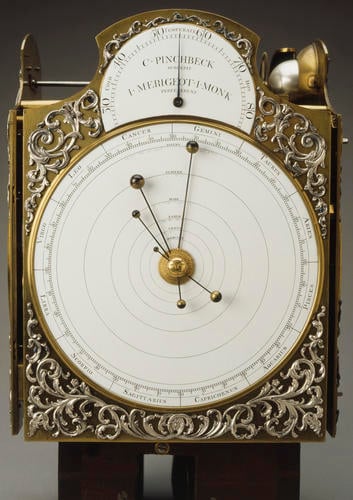

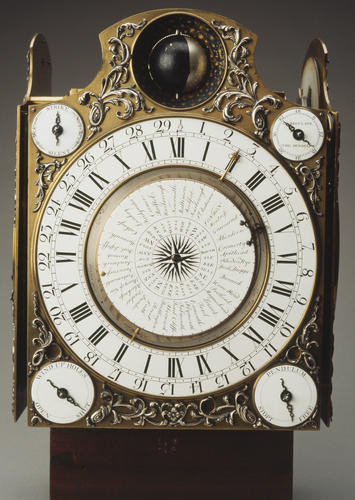

Like the Eardley Norton astronomical clock of 1765, the mechanism of this 4-sided astronomical clock is designed to impress with its comprehensiveness and complexity, and the case with its superb quality and glamorous materials. The movement is a 3-train spring driven with fusee and chains, maintaining power on the going train and a dead beat jewelled pallet escapement. At each ¼-hour the clock 'Ting-Tangs' on 2 bells (1 at the ¼ hour, 2 at the ½ hour, 3 at the ¾ hour and 4 times at the hour) followed by the appropriate hour on the third bell. The striking motion work is of the 'Flirt' action type with ¼ and hour racks.

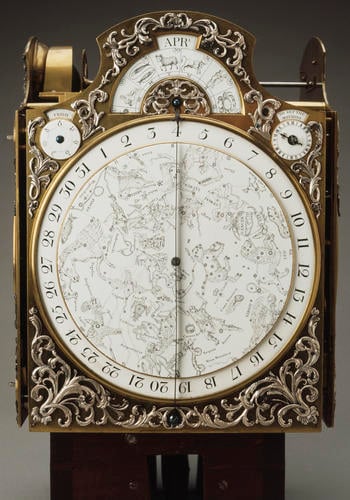

The four principal dials operate almost identically on both clocks, the main differences being that on this Pinchbeck clock the calendar dial incorporates a planisphere, the orrery dial includes a thermometer and the dials recording the time at locations round the world (relative to mean time and high and low water at seaports) vary in some of the places named. The enamelling of the dials on the two clocks compares very closely in style and may be by the same hand. The mechanism was constructed by Pinchbeck, the King’s clockmaker, with the assistance of John Merigeot (apprenticed 1742) and John Monk (apprenticed 1762).

On a visit to Pinchbeck’s workshop in Cockspur Street, London on 29 January 1768 to inspect the newly completed clock, the diarist Lady Mary Coke noted that the design was ‘partly His Majesty’s and partly Mr Chambers his Architect’. Although the extent of George III’s contribution is difficult to judge, Chambers’s involvement could be inferred from the temple-like appearance and laurel-draped urns of the clock case, resembling in miniature a building such as the Casino at Marino (begun in 1758 to Chambers’s designs) and is confirmed by the existence in the Soane Museum of a highly finished design drawing by Chambers, varying in some details from the finished clock. No record of payment for the clock is recorded, nor is the name of Pinchbeck’s case-maker known. Whoever was responsible had access to a metalsmith of distinction - possibly Diederich Nicolaus Anderson, as has been suggested. The jewel-like gilt bronze and silver mounts are of outstanding quality and remarkable for the precision of their casting and chasing.

In George III’s time the clock was kept in the Passage Room, which probably lay at the centre of his apartment at Buckingham House, on the west (garden) front. It was originally mounted on a circular tray resting on the head and upraised hands of a bearded herm pedestal of carved giltwood, perhaps also designed by Chambers. The pedestal, which was 167.6 cm (66 in.) high, is recorded in the Pictorial Inventory but no longer survives in the Royal Collection.

Catalogue entry adapted from George III & Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste, London, 2004Provenance

Included in the Pictorial Inventory of 1827-33 – RCIN 934879. The inventory was originally created as a record of the clocks, vases, candelabra and other miscellaneous items from Carlton House, as well as selected items from the stores at Buckingham House, the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, Hampton Court and Kensington Palace for consideration in the refurbishment of Windsor Castle.

-

Creator(s)

(clockmaker)(clockmaker)(metalworker)Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Tortoiseshell, oak, gilt bronze, silver, brass, steel and enamel

Alternative title(s)

Table clock