-

1 of 253523 objects

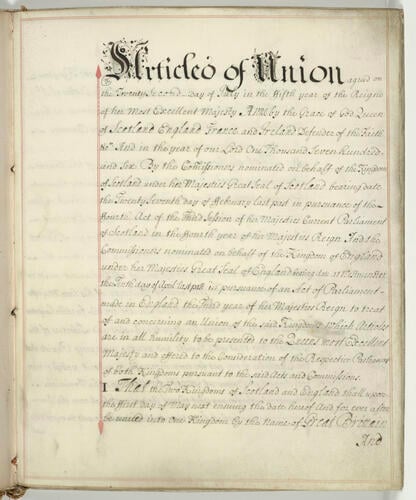

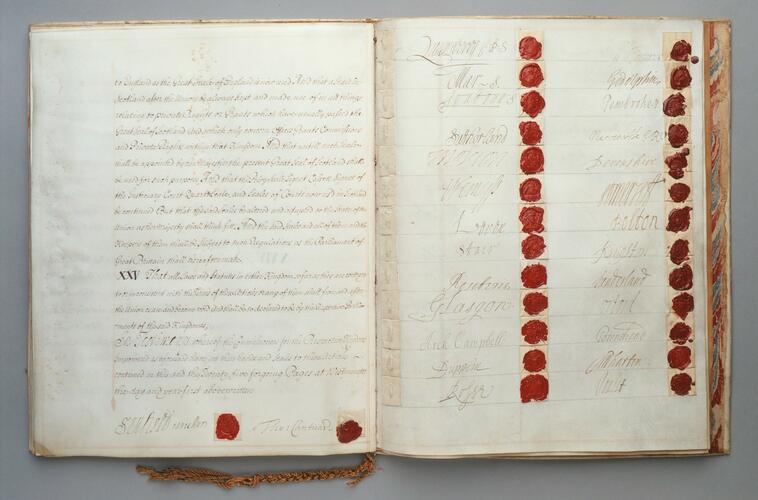

Articles of Union between Scotland and England, 1706 1706

Ms. on vellum; signed and sealed 22 July 1706. 16 leaves in 8 conjoingt pairs: unnumbered. ff.15-16 blank | 38.6 x 31.0 x 2.3 cm (book measurement (conservation)) | RCIN 1142244

![Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706] Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706]](https://col.rct.uk/sites/default/files/styles/rctr-scale-1300-500/public/collection-online/7/b/1058799-1650536629.jpg?itok=iUDoqC54)

Great Britain

Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706] 1706

![Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706] Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706]](https://col.rct.uk/sites/default/files/styles/rctr-scale-1300-500/public/collection-online/6/3/222531-1319822103.jpg?itok=5_gH0uMg)

Great Britain

Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706] 1706

-

One of two known copies of the Articles of Union signed by the Scottish Parliament in January 1706, evidenced by the signatures and seals of the Scottish commissioners preceding those of the English. Another copy can be found in the National Records of Scotland (ref. SP13/209). Bound in vellum, gold-tooled: panels with inexpertly-applied floral motifs: spine pierced and threaded with red and blue silk cords plaited in a tail below the book.

Although the Crowns of England and Scotland were united in 1603, when James VI acceded the English throne as James I, attempts by the King to encourage a more formal union were abandoned due to opposition from both sides. However, by the end of the seventeenth century, economic and political differences between the two nations, as well as threats from increasing French power in Europe, brought the matter to a head.

Following the ‘Glorious’ Revolution of 1688, many in Scotland were angered at the English Parliament’s decision to declare James VII & II (r. 1685-88) as having abandoned his kingdoms. The new monarchs, William III (r. 1689-1702) and Mary II (r. 1689-1694), were seen as having usurped the Scottish throne without consent and groups, primarily in the Highlands, began to organise resistance. These groups became known as ‘Jacobites’, after the Latin for ‘James’, and from 1692 William undertook a brutal campaign of suppression against the clans that had refused to swear an oath of allegiance by December the previous year.

In concert with this, a series of failed harvests between 1695 and 1699 saw famine spread across Scotland. An estimated 5-10% of the population died or emigrated, mainly to Ireland, while much of Scotland’s capital was invested in the import of grain to feed the starving nation. Rather than enacting agricultural reforms along the English model as recommended in treatises published by Scottish authors from the 1660s, Scots instead began to believe that the establishment of an overseas empire would provide the much-needed income. Seeing that both England and the Netherlands had benefitted from colonial possessions, a consortium of Scots, led by William Paterson (1658-1719), who had recently assisted in the foundation of the Bank of England, established the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies and sought sponsorship. The Company planned to establish a colony on the Isthmus of Darien (now Panama) to take advantage of trade coming from both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Offering wild speculations about the benefits of such a scheme, the Company was able to persuade many Scots from all walks of life to invest and by the beginning of 1699, around a third of Scotland’s wealth was bound up in the success of Paterson’s ‘Darien Scheme’.

The ships departed from Leith that summer and a small settlement named New Edinburgh was founded at Darien some months later. Finding the land swampy and disease-ridden, the colonists soon began to fall ill and die. Having travelled with goods of little value to passing ships, the endeavour would have likely always struggled, but it was soon compounded by William III’s enforcement of protectionist policies that forbade any English or Dutch ships from trading with the Scottish colony. The King had begun secret plans to maintain Spanish goodwill and was concerned that if he was shown to support the scheme, it would anger Spain, who claimed the territory. Such actions risked driving the Spanish closer to William’s great rival Louis XIV of France and upsetting the European balance of power. On hearing news of a planned Spanish expedition from Cartagena to destroy the colony and faced with ongoing English protectionism and rampant disease, the surviving colonists left Darien and returned home. Only a handful of the original contingent (including Paterson) returned to Leith in 1701 and the vast fortune invested into the Company was lost, plunging Scotland further into financial turmoil.Also in 1701, the English Parliament passed the Act of Settlement following the death of Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (1689-1700), the only surviving child of Princess Anne, sister to Mary II and heir to the throne. The Act defined the succession following Anne’s decease, removing the exiled Catholic Stuarts and declaring Electress Sophia (1630-1714), daughter of James VI & I’s only daughter Elizabeth (1596-1662), and her successors as heirs. This further angered Scotland and in 1703, by which time Anne (r. 1702-14) had become Queen, the Scottish Parliament passed the Act of Security. This act declared that the Scottish Parliament had the right to select Anne’s successor and stipulated that it would only choose the same as England if Scotland was granted free access to English markets. Such a declaration roused fears in England that Scotland would end the union of the crowns and choose to return the exiled Stuarts to the throne, risking the reestablishment of the ‘Auld Alliance’ with France, which would leave England’s northern border vulnerable.

In response, the English Parliament passed the Aliens Act in 1705 to counter Scotland’s reassertion of its independence. The act gave the provision for a royal commission to be established in both England and Scotland to seek a formal union between the two kingdoms.

Meeting in London in April 1706, the commissioners spent four months negotiating the terms of the treaty and what form the proposed union might take. While both parties agreed on maintaining the succession and on establishing freedom of trade and movement, English negotiators sought the total abolition of the Scottish Parliament and planned for government to be centred in Westminster. In contrast, the Scottish commissioners argued for the preservation of their government and the formalisation of a system where Scottish sovereignty was guaranteed. Such terms were unacceptable to England and after further negotiations, English plans won out, but with the provision of additional seats granted to Scottish representatives (45 in the Commons, 16 in the Lords) in the new Parliament of Great Britain. Sitting peers in the Scottish Parliament were to receive compensation for losing their seats and the English government would loan Scotland a vast sum of almost £400,000, known as ‘The Equivalent’ to support the Scottish economy taking on its share of debt and to repay the investments made by Scots in the failed Darien Scheme. The money was not a gift and was to be paid back to the Treasury through Scottish duties on wines, beers and spirits.

The treaty was approved in London on 16 July 1706 and copies were drawn up for debate in Edinburgh. However, in Scotland, the prospect of a union with England drew much public anger and pamphlets attacking the Scottish Parliament for what was seen as a national betrayal were printed. Riots and protests in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dumfries were reported by the English writer and spy Daniel Defoe as the Scottish Parliament sat to debate the union from 3 October 1706. Even though it was largely composed of members who had passed the Act of Security three years before, English provisions (including the Equivalent, guarantees of free trade and the continued independence of the Scottish legal system) seemed to have swayed many members in favour of the treaty and soon rumours began to spread among the public that English agents were bribing politicians for their support. Such beliefs remained strong in Scottish minds and later writers such as Sir Walter Scott and Robert Burns wrote of the Scottish Parliament being ‘bought and sold for English gold’ in the months leading up to the union.On 15 October, the Scottish Parliament agreed to proceed with the reading of the terms of the treaty by a large majority. The articles were read through the rest of October, with votes on each commencing from 1 November. As the terms became known to the public at large, outcry grew, and official addresses were delivered across Scotland in protest. Such addresses were read aloud at the beginning of each parliamentary session but business continued as usual and on 16 January 1707, the act was passed by a majority of 41. The terms were then read in Westminster, where they were passed without opposition by 4 March and on 6 March the treaty received royal assent.

When the act came into force on 1 May 1707, it was met with a melancholic atmosphere in Scotland, with church bells in Edinburgh reported as ringing the tune ‘Why should I be sad on my wedding day’. In England, meanwhile, Queen Anne attended a Thanksgiving service at St Paul’s Cathedral and public rejoicing was witnessed across London, with Scottish writers noting ‘the whole day was spent in feasting, ringing of Bells and illuminations’.Further reading

Daniel Defoe, The History of the Union between England and Scotland (London, 1786)Michael Fry, The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707 (Edinburgh, 2006)

Allan I MacInnes, Union and Empire: the making of the United Kingdom in 1707 (Cambridge, 2007)

Paul Henderson Scott, The Union of 1707: why and how (Edinburgh, 2006)

Christopher A Whatley, Bought and Sold for English gold?: Explaining the Union of 1707 (East Linton, 2001)

Christopher A Whatley, The Scots and the Union (Edinburgh, 2007)

Provenance

In 1854, Sir Geers Henry Cotterell, 3rd Bt. of Garnons, Hertfordshire, found the Treaty amongst his possessions, without any record of any provenance. It was presented by his son, Sir John Richard Greers Cotterell, 4th Baronet, to King Edward VII in June 1906

-

Creator(s)

(corporate author)(corporate author)Acquirer(s)

-

Medium and techniques

Ms. on vellum; signed and sealed 22 July 1706. 16 leaves in 8 conjoingt pairs: unnumbered. ff.15-16 blank

Measurements

38.6 x 31.0 x 2.3 cm (book measurement (conservation))

Category

Subject(s)

Alternative title(s)

Articles of union [between Scotland and England, 1706].