-

1 of 253523 objects

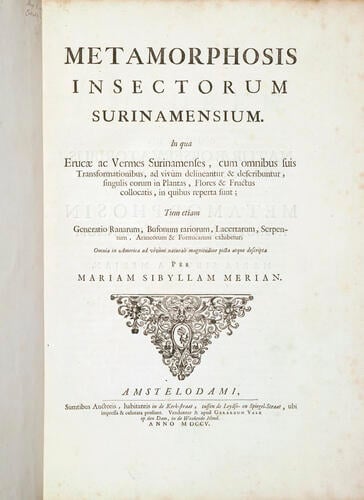

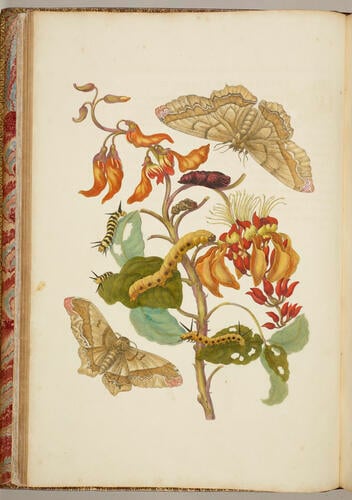

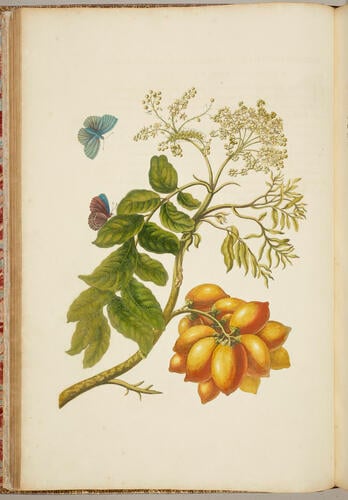

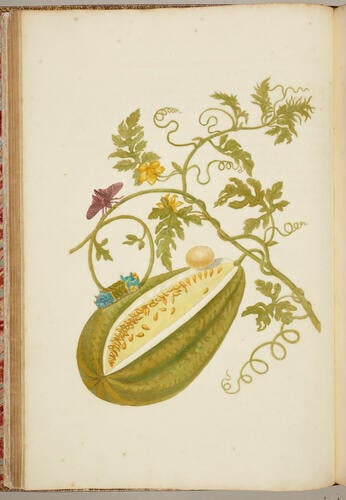

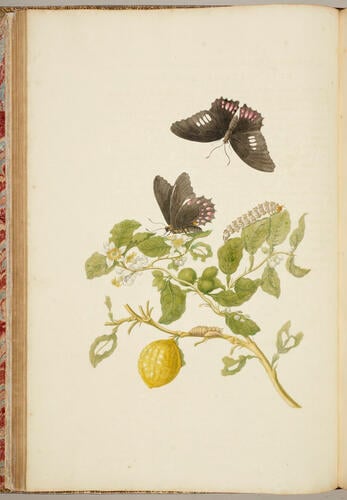

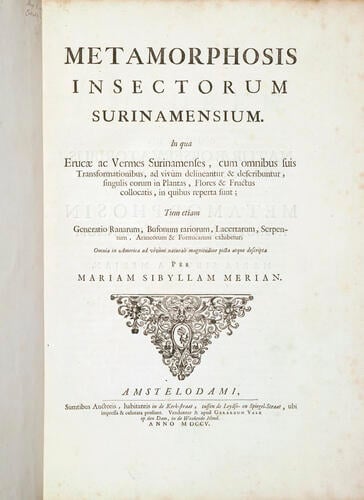

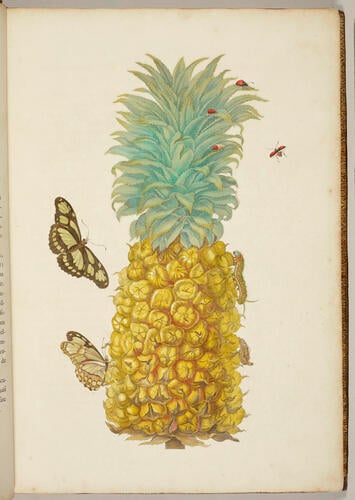

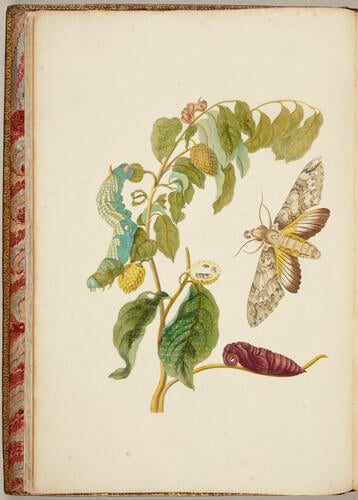

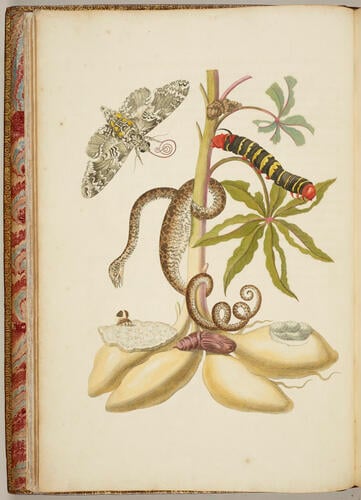

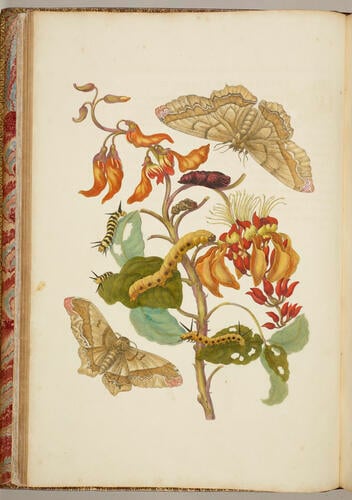

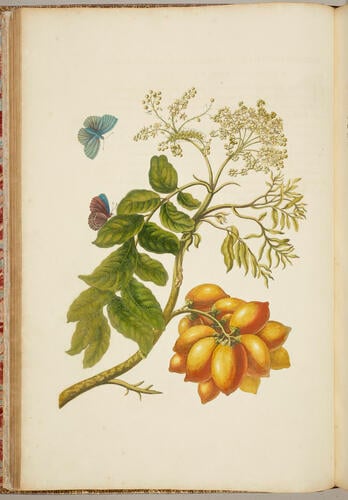

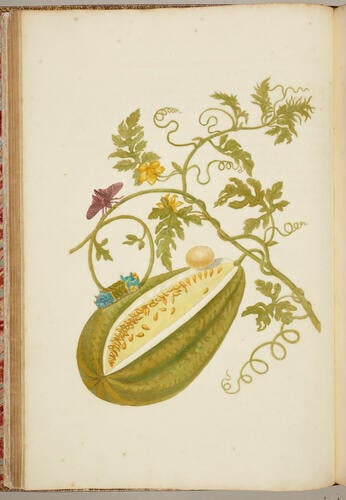

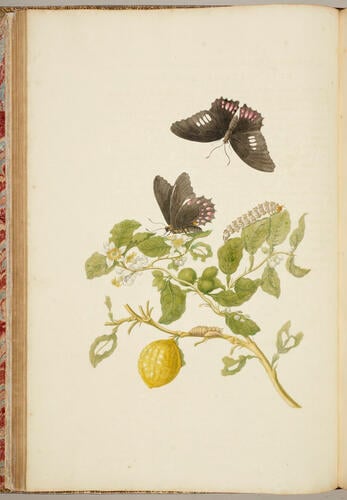

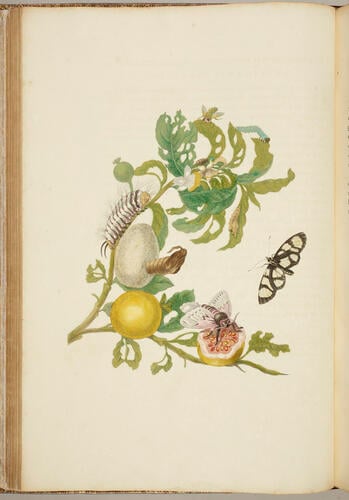

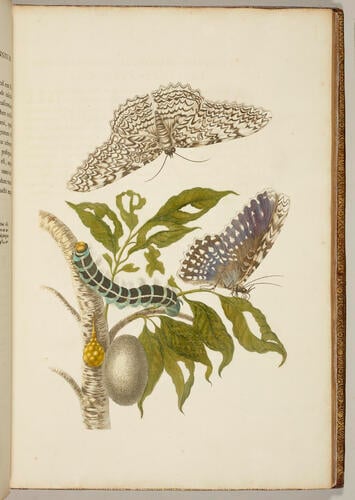

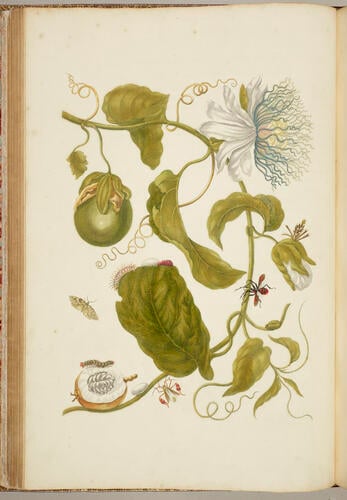

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium 1705

53.0 x 4.0 cm (book measurement (inventory)) | RCIN 1085787

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian 1705

-

Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium is an exceptional example of the important, yet often hidden, contributions made by women naturalists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Born to a family of prominent German printer-publishers, Merian was introduced to art and publishing from a young age. Her father, Matthaus Merian the Elder (1593-1650), had made money from the production of lavish illustrated accounts of Protestant voyages and topographical works with engraved views of European cities (Topographia Germaniae, 38 parts, 1642-c. 1654). Following his death, Merian’s mother, Johanna Sibylla Heine (d. 1690), married the flower painter, Jacob Marrell (1614-81), who taught the young Merian drawing and fostered her interests in the natural world. From the age of 13, she began collecting and observing insects, making detailed observations of caterpillars and the stages of their transformation.

In 1665, Merian moved to Nuremberg on her marriage to Johann Graff, her stepfather’s apprentice, where she taught drawing to the daughters of the local elite. Although the marriage seems to have been an unhappy one, it was in Nuremberg where she published her first natural history works: a pattern-book of flower engravings (Florum, three parts, 1675-80, later published as one volume with the title Neues Blumenbuch) and a volume on the metamorphosis of caterpillars (Der Raupen Wunderbarer Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumen, ‘The Wondrous Transformation of Caterpillars and their Remarkable Diet of Flowers’, two parts, 1679 & 1683). After the death of Marrell, Merian and her daughters moved in with her mother, and, in 1685, the family moved to Friesland to join a Labadist community at Wiuwert. As a part of the community, Merian had access to the collection of South American flora and fauna collected by the group's patron Cornelis van Sommelsdijk at Waltha Castle, which sparked her interests in the exotic wildlife being encountered overseas. This was only enhanced when, in 1691, Merian and her daughters moved to Amsterdam, where they became associated with the scientific circles of the city. Granted access to the institutions and collections in Amsterdam, Merian wrote of the ‘wonderment’ she experienced on seeing ‘beautiful creatures brought back from the East and West Indies’.

In 1699, she received permission to travel to a Labadist colony recently established in Suriname. Accompanied by her youngest daughter, Dorothea Maria Graff (1678-1743), Merian made the most of her time in South America, making repeated expeditions to the interior, to observe and collect new specimens to draw from life. She employed enslaved and Indigenous people to help with cutting back vegetation and to carry heavy luggage. She also sought their advice when encountering new species and wrote of the culinary and medicinal uses of tropical plants.

The colonists viewed Merian’s passion with suspicion and Merian wrote of her dislike of their clamour for sugar and their treatment of enslaved and Indigenous people, noting in her description of the peacock flower:'The Indians, who are not treated well in the service of the Dutch, abort their children with these [seeds], not wanting them to be slaves like themselves…[enslaved women] sometimes even take their own lives, due to the typical harsh treatment they receive.'

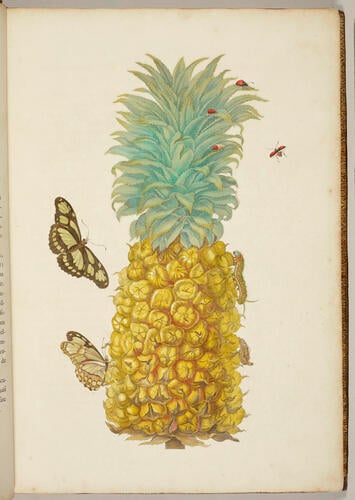

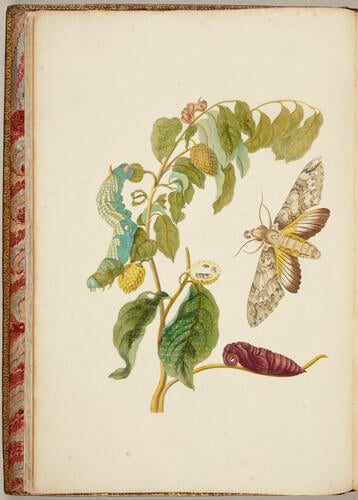

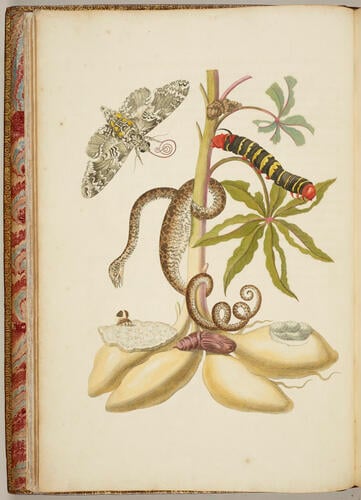

Merian and Dorothea returned to Amsterdam in 1701 and quickly established a workshop, working with her eldest daughter Johanna Helena Herolt (1668-c. 1723), to turn the multitude of sketches, dried plants and insects, preserved reptiles and amphibians and copious notes into a published volume. The trio worked up Merian's drawings into detailed compositions on vellum, painted with bold watercolour and body colour. The vibrant images were unsigned rendering it difficult to identify which parts of the drawings were done by Merian herself and which were done by her daughters. The completed watercolours were then engraved, printed and published with the innovative inclusion of lively descriptions on the facing page following the style used in the catalogue of the Hortus Botanicus at Amsterdam (Horti Medici Amstelodamensis, 2 vols 1697 & 1701, RCINs 1057108-9).

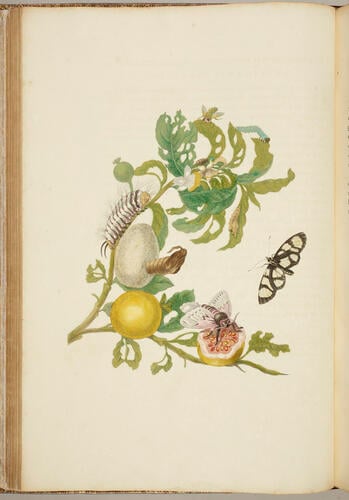

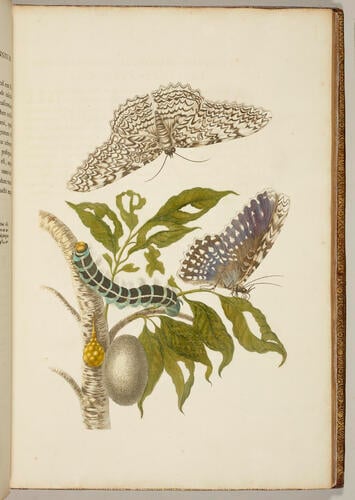

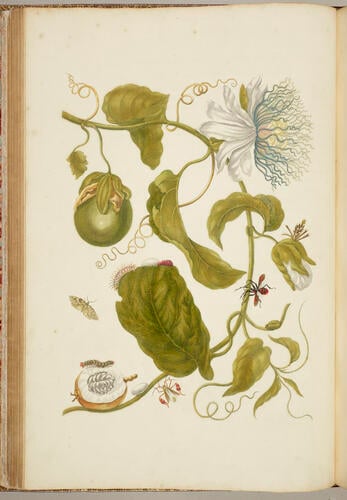

Merian’s depictions of reptiles, amphibians, spiders, ants, beetles, butterflies and moths were remarkable for the accuracy she demonstrated and are among the most important contributions to the early history of herpetology and entomology. Unlike other early works on the life-cycles of moths and butterflies, Merian ensured that the creatures were drawn with the plants upon which they relied, describing for the first time the limited number of species that provided the correct nourishment for different larvae.

Merian and her daughters oversaw all aspects of production and ensured that the book would be available in a variety of formats for potential subscribers. The illustrations could be purchased either coloured or not and the text was available in both Dutch and Latin. Merian also mooted a possible English translation to present to Queen Anne, but it appears that nothing came of the idea. The resulting work was published in 1705, and was dedicated ‘to all lovers of nature’. The first book to concentrate on the natural history of Suriname, it was hugely successful, and the skills of Merian and her daughters were quickly recognised by contemporaries. Johanna Herolt found work on her own projects before travelling to Suriname herself in 1711, supplying the workshop with additional drawings. Dorothea, meanwhile, travelled to St Petersburg following Merian's death in 1717 and her marriage to the art dealer George Gsell, where she taught flower and animal painting to the Russian court and served as curator of Peter the Great's cabinet of curiosities, the Kunstkamera.

Of the various versions of Metamorphosis available, it was the deluxe editions that were the most special. These featured counterproof illustrations: a technique of transfer printing employed by Merian to supreme effect. This involved placing a sheet of vellum or paper over a just-inked print so that the resulting faint image was the same orientation as the original watercolour. The faint lines reflected the original pencil marks and the plates were then coloured delicately by hand by Merian or her daughters. The Royal Collection contains two such examples of Merian’s counterproofing. The present volume, printed on paper with the accompanying text in Latin, was acquired by William IV in 1835 from the sale of the botanist William Forsyth (c. 1772-1835). Another set, on vellum with an accompanying manuscript of the descriptions in French, was acquired by George III (RCINs 921148-921241. Manuscript, RCIN 809357).Provenance

From the collection of the botanist William Forsyth. Acquired by William IV at the sale following his death in 1835.

-

Creator(s)

(printer)Acquirer(s)

-

Measurements

53.0 x 4.0 cm (book measurement (inventory))

Category

Alternative title(s)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. In qua erucae ac vermes Surinamenses, cum omnibus suis transformationibus, ad vivum delineatur & describuntur, singulis eorum in plantas, flores & fructus colloeatis, in quibus reperta sunt; tum etiam generatio ranarum, busonum rariorum, lacertarum, serpentatum, araconium & formicarium exhibitur, omnia in America ad virum naturalis magnitudinae picta atque descripta / per Mariam Sibyllam Merian.