-

1 of 253523 objects

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare. 1632

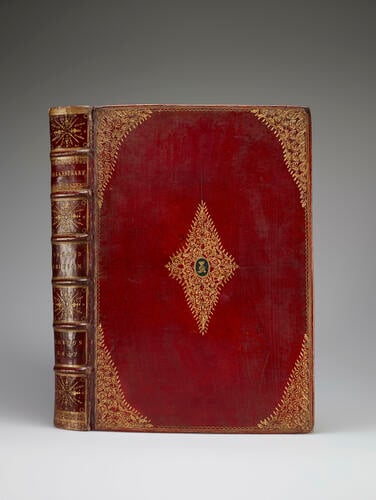

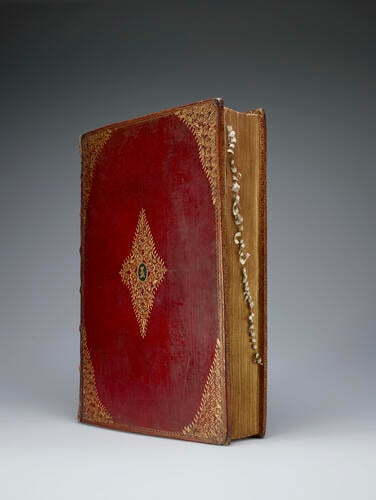

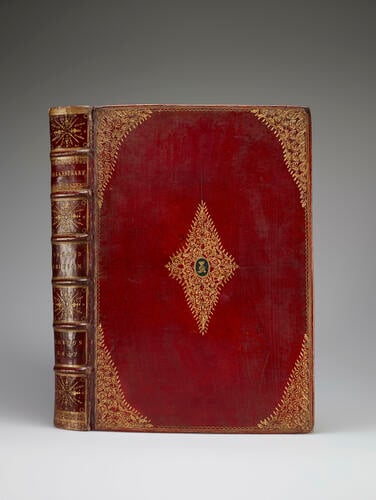

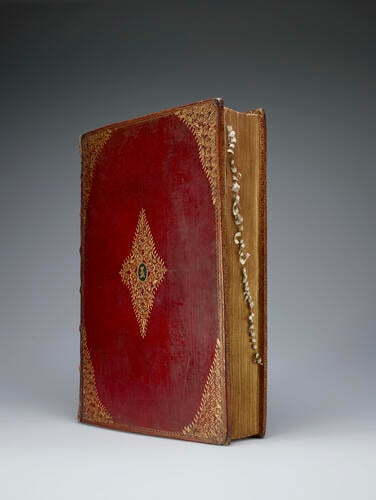

33.5 x 23.7 x 4.8 cm (book measurement (conservation)) | RCIN 1080415

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true originall copies / William Shakespeare 1632

-

Charles I, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, read this copy of William Shakespeare’s collected plays while imprisoned at Windsor Castle during the civil wars, in the days before he was put on trial and executed in 1649. Inside it he wrote ‘Dum Spiro Spero’, Latin for ‘while I breathe, I hope’. He gave it to his attendant, Thomas Herbert, through whose family it probably passed until it came to be owned by a series of book collectors. In 1800 it was purchased by George III, who also wrote in the book. Both kings’ interactions with the book illuminate their lives and characters. This historically significant book is now in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, having returned to the place where Charles I read and wrote in it.

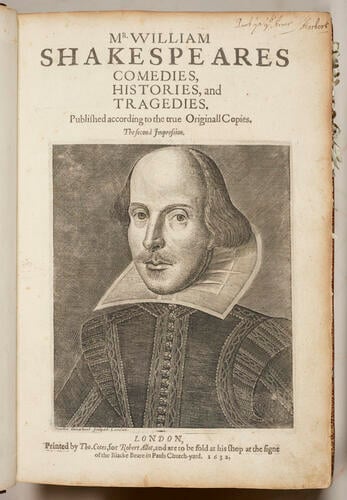

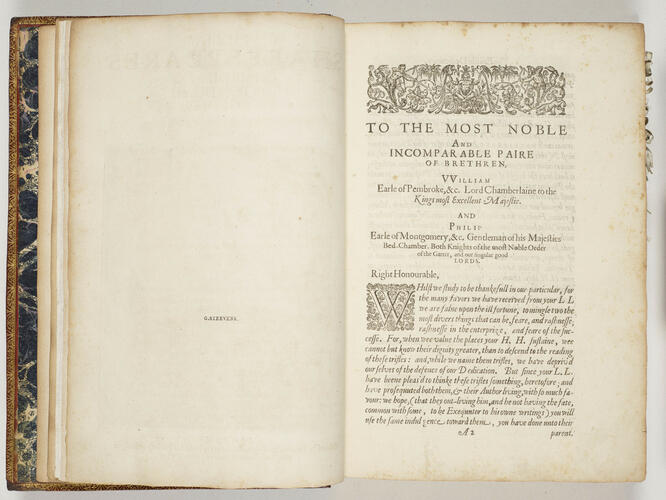

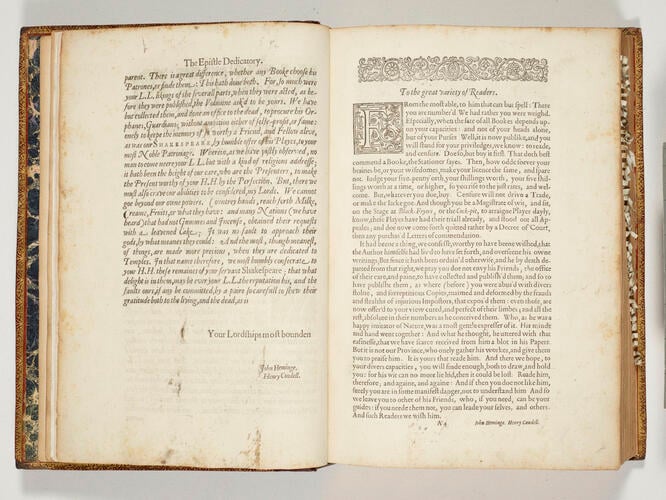

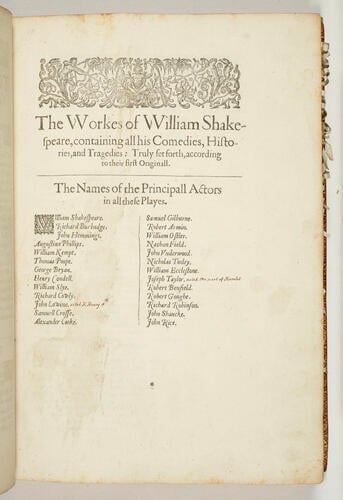

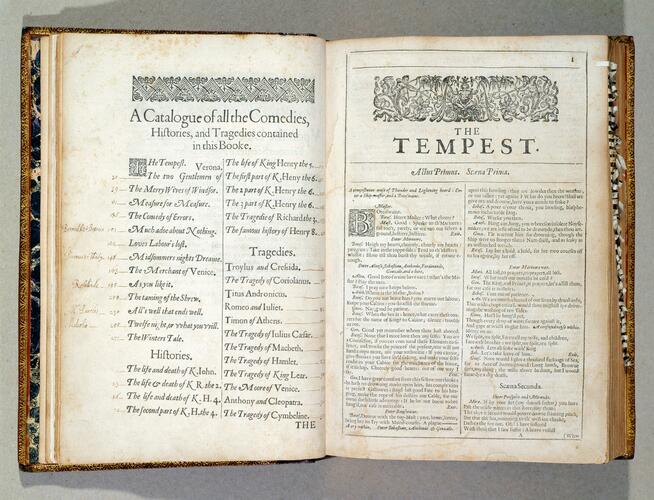

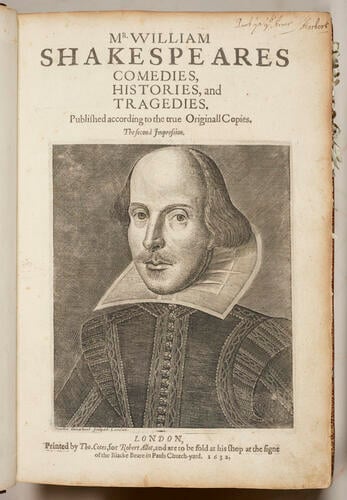

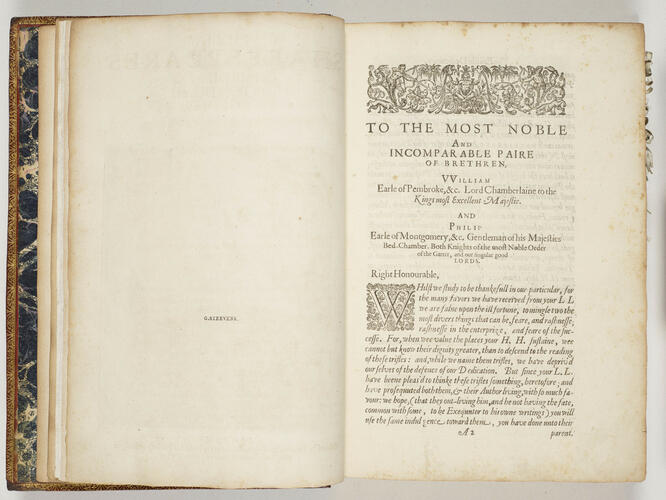

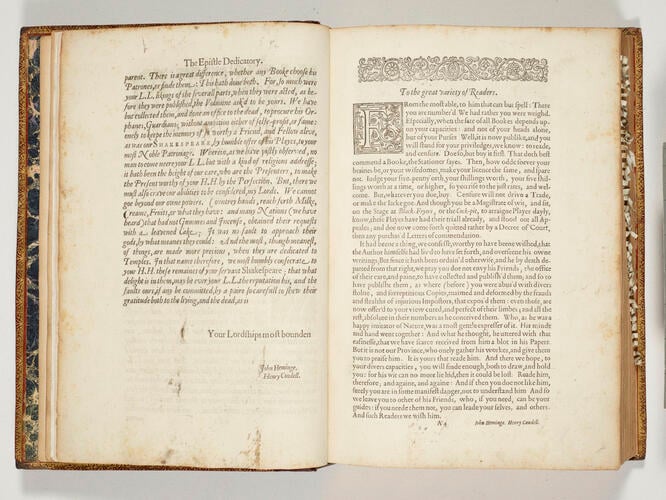

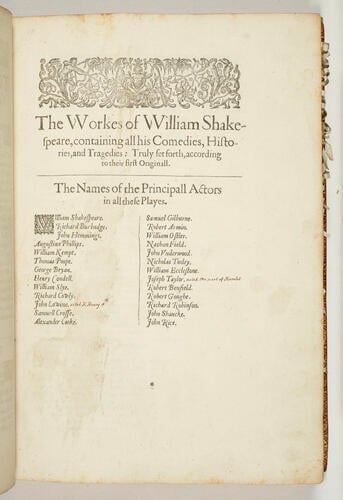

This is the second edition of William Shakespeare’s collected plays, published in 1632 and known as the Second Folio. It was produced nine years after the First Folio, which gathered Shakespeare’s plays in a single volume for the first time in 1623. Issued posthumously through the efforts of Shakespeare’s fellow actors John Heminges and Henry Condell, the First Folio brought together previously unpublished plays, and plays that were otherwise circulating in quartos – a more ephemeral, smaller format. The Royal Library has a copy of the First Folio (RCIN 1047467).

The Second Folio was published after the rights to many of Shakespeare’s plays had been passed on from those who had held them at the publication of the First Folio. The principal of those who now held rights in the plays was Robert Allot, a bookseller and publisher. The printer of the Second Folio, Thomas Cotes, printed the greatest proportion of copies for Allot to sell at his shop at the sign of the Black Bear in the church yard of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, while the holders of rights to fewer plays had smaller proportions. The copy owned by Charles I is one of those printed for Allot. The Second Folio bibliographer William B. Todd recorded it as Ia3, or first issue, first state, third variant. This means that it is not a particularly rare issue, being one of many printed for Allot, but it is considered to be a good copy, produced in the year stated on the title page. (Other issues give a false date of 1632, and are thought actually to have been printed in 1641.)

Assuming that Charles I acquired his copy of the Second Folio on its publication in 1632 – and there is no evidence in the book of there being any previous owners – this was at a time when his reign appeared peaceful, and his life seemed happy. He had paused contentious efforts to wage war internationally, and his son and heir Charles (later Charles II), had been born in 1630, with his second child, James (later James II), due to be born in 1633. William B. Todd suggested that the Second Folio was given to the king in the spirit of legal deposit, but, given Charles’s general enthusiasm for collecting, and interest in Shakespeare in particular, he may have had more agency in the acquisition of the book than Todd suggests.

The acting company to which William Shakespeare belonged, the King’s Men, performed at the court of James I and VI, Charles’s father. Shakespeare would have been present on occasion, if not acting. It is likely that a young Charles was also present, watching Shakespeare’s plays, and probably aware of the playwright himself. Perhaps this interaction informed Charles’s later partiality for reading Shakespeare.

The king’s reading of the plays of Shakespeare while imprisoned during the civil wars is well documented. In the news publication Perfect Occurrences of Every Daies Journall in Parliament, 22 to 30 December 1648, it was reported from Windsor that ‘the King is pretty merry, and spends much time in reading of Sermon Books, and sometimes Shakspeare and Ben: Johnsons Playes.’ John Milton also marked Charles I’s reading of the playwright. In 1649 Milton was commissioned by the Commonwealth government to write Eikonoklastes, the official reply to Eikon Basilike, a book published at the time of Charles I’s execution and believed in part to have been written by the king himself. A defence of his actions during the civil wars, it was proving popular, and was generating sympathy for the king’s cause. In Eikonoklastes, Milton finds parallels between Charles I and Shakespeare’s villain Richard III, and writes of William Shakespeare being to Charles I ‘the Closest Companion of these his solitudes’. This was not intended to be a compliment, despite the fact that the first book in which Milton ever had one of his poems published was Shakespeare’s Second Folio.

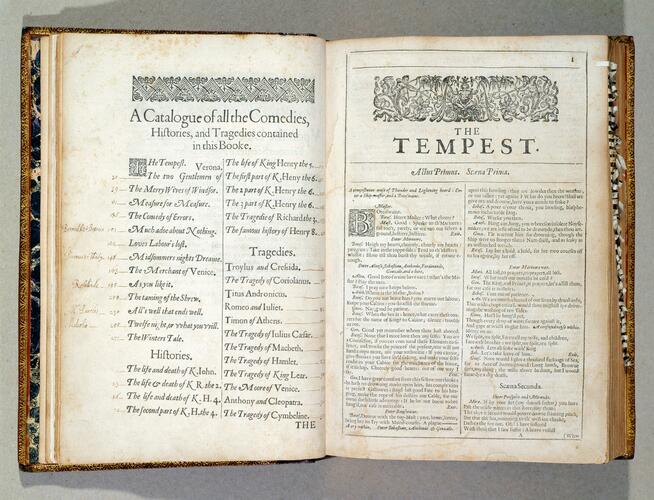

Although imprisoned from May 1646 until his execution in January 1649, Charles I was, until he was put on trial, largely free to move around the castles and houses in which he was held. When at Windsor Castle he stayed in the rooms he had always used, and he was free to walk on the North Terrace. He was permitted books from his royal library from at least January 1647, and it is presumably at this point that he began to keep his copy of Shakespeare with him. Annotations on the contents page, previously thought to have been by Ben Jonson, are now confirmed to be in Charles’s hand. The printed page does not give page numbers for the plays: Charles added these in. He also wrote the names of some of the characters alongside a selection of the comedies, such as ‘Bennedik & Betrice’ next to Much adoe about Nothing, and ‘Rosalinde’ against As you like it. The king’s interaction with the comedies counters Milton’s accusation that he was reading Shakespeare in order to mine the history play Richard III for content for his Eikon Basilike.

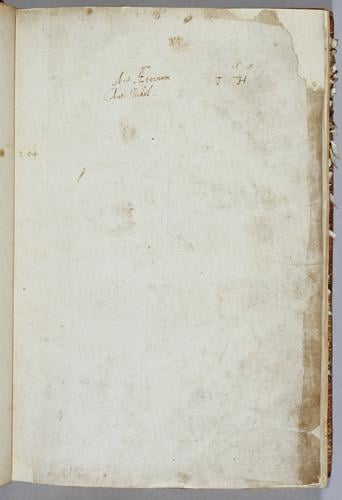

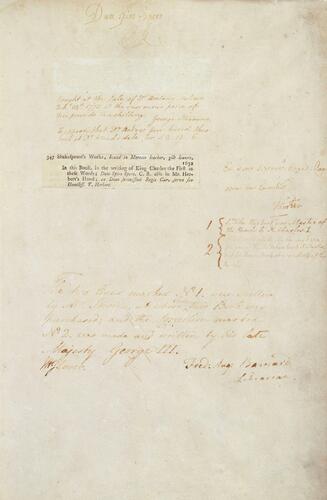

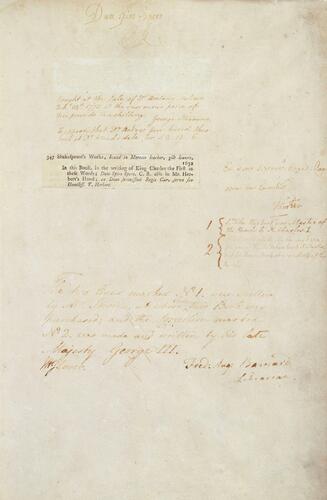

The plays themselves are not annotated by Charles. The only other note in his hand is on the fly leaf: ‘Dum Spiro Spero’, the poignant ‘while I breathe I hope’ motto he wrote in books he was reading while imprisoned. Nine other books are known to survive with Charles’s handwritten ‘Dum Spiro Spero’ motto, including Godfrey of Boulogne, or, The Recoverie of Jerusalem, translated by Edward Fairfax from Torquato Tasso’s original Italian, and Arrigo Caterino Davila's The Historie of the civill warres of France.

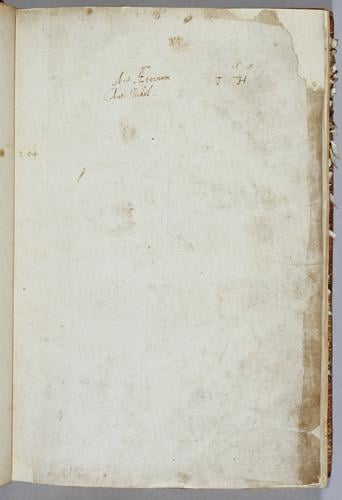

Another book annotated by Charles with ‘Dum Spiro Spero’, Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queen, was given or lent to him by Thomas Herbert, one of his closest attendants while he was imprisoned. Herbert, a courtier who followed the protocols important to the king, but who was also a confirmed supporter of Parliament, was the perfect choice. Herbert recalls the king reverently in his Memoirs, emphasising Charles’s piety and the trust the king placed in him. It was he who had charge of the king’s books while he was imprisoned, and it was to him that Charles I’s copy of Shakespeare’s Second Folio passed. On the same fly leaf of Charles’s ‘Dum Spiro Spero’ motto, Herbert recorded that the book was given to him by King Charles, signing it his humble servant, T. Herbert. Whether the king really did give Herbert the book, or Herbert appropriated it, is debated. Further inscriptions by Herbert in the Second Folio are ‘Aut Aternum Aut Nihil’ (‘eternity or nothing’), and his family motto, ‘Pawb yn y Arver’ (Welsh for ‘everyone his own customs’).

Thomas Herbert died in 1682 and the Second Folio presumably passed through his family. The next recorded owner is Richard Mead, physician to George II and owner of one of the largest collections of books, art and antiquities in the first half of the eighteenth century. Following Mead’s death, his 10,000 books were sold in a 56-day-long auction by Samuel Baker. On the 55th day, 7 May 1755, Charles I’s Second Folio was sold for £2 12s 6d, a great deal less than a contemporary edition of Shakespeare’s plays in six volumes fetched on the same day. The preference for modern editions and the bookseller’s failure to record the provenance of Charles I’s Second Folio reduced its value.

The buyer was another physician and book collector, Anthony Askew. By the time of the sale of his books in 1775, the Second Folio was worth considerably more, particularly as its provenance was noted in the catalogue. The Shakespeare scholar George Steevens bought it for £5 10s, an ‘enormous price’ as he wrote in the Folio itself.

Steevens is often remembered for hoaxes and forgeries, but his contribution to the field of Shakespeare scholarship was substantial, and his library contained numerous important early editions of Shakespeare’s works. Many of his books in the catalogue of his sale, Bibliotheca Steevensiana (1800), are described as having notes added by Steevens, and Charles I’s Second Folio is no exception. ‘G. STEEVENS’ is stamped on the back of the title page. On a fly leaf, Steevens recorded where he purchased it and how much he paid. He also wrote underneath Thomas Herbert’s inscription that the latter was the king’s Master of the Revels. It was probably Steevens who added a print facing the title page. Published in 1794, it is after a painting of Shakespeare known as the Felton Portrait. Like many other portraits of Shakespeare it is of uncertain authenticity, but Steevens is known to have believed in it.

Steevens’s ‘enormous price’ of £5 10s is dwarfed by the amount paid for Charles I’s Second Folio at the Bibliotheca Steevensiana sale. A Mr Nicol bid against the book collector Charles Burney (brother of the writer Fanny Burney). As the bidding reached £18 8s Burney became aware that Nicol was acting on behalf of the king, George III, and withdrew. In gratitude, George III gave Burney the copy of the Second Folio from his royal library (it is now in the New York Public Library).

Charles I has been characterised as a king who liked to correct reports and dispatches, and so it is fitting that George III made a correction in his predecessor’s book. Where Steevens had written that Thomas Herbert was Master of the Revels, George III has put him right, noting underneath that Thomas Herbert was actually Groom of the Bedchamber, and that it was his relative Henry Herbert who had been Master of the Revels.

A bibliophile, George III amassed a notable library in Buckingham House. When his son, George IV, remodelled Buckingham House into Buckingham Palace, he gave his father’s library to the British Museum (it is now known as the King’s Library, at the heart of the British Library). However, George IV retained his father’s most prized books, including Charles I’s Second Folio.

In most book collections which hold both a First Folio and a Second Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, the First Folio would be the volume most admired. Yet the levels of interaction from key historical figures visible in the Royal Library’s Second Folio elevate it to a treasure of national significance. Through the evidence of this book, two kings are brought more vividly to life.

Further Reading

• Samuel Baker, Bibliotheca Meadiana (London, 1754)

• S. Baker and G. Leigh, Bibliotheca Askeviana (London, 1774)

• Sir Thomas Herbert et al, Memoirs of the Two Last Years of the Reign of that Unparallel’d Prince of Ever Blessed Memory, King Charles I (London, 1702)

• Thomas King, Bibliotheca Steevensiana (London, 1800)

• John Milton, Eikonoklastes (London, 1649)

• William B. Todd, ‘The Issues and States of the Second Folio and Milton's Epitaph on Shakespeare’, in Fredson Bowers, ed., Studies in Bibliography: papers of the Bibliographical Society, v. 5, 1952-3 (Charlottesville, 1952), pp. 81-108.

• H. Walker, Perfect Occurrences of Every Daies Journall in Parliament: proceedings with His Majesty and other moderate intelligence…from Fryday December the 22 to Fryday December the 30 1648 (London, 1648)

• Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (www.oxforddnb.com)Provenance

Charles I; passed to Sir Thomas Herbert; probably owned by Herbert's descendants before being sold; probably in the collection of Richard Mead; probably purchased at his sale (lot 1744, 7 May 1755) by Anthony Askew; purchased at his sale (lot 347, 14 February 1775) by George Steevens; purchased at his sale (lot 1314, 21 May 1800) by George III

-

Creator(s)

(publisher)(printer)Acquirer(s)

-

Measurements

33.5 x 23.7 x 4.8 cm (book measurement (conservation))

Category

Other number(s)

ESTC : English Short Title Catalogue Citation Number – ESTC S111233Bibliographic reference(s)

English Monarchs and their books / TA Birrell pp. 44-7

Alternative title(s)

Second Folio