-

1 of 253523 objects

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies. 1623

40.4 x 25.6 x 6.8 cm (book measurement (conservation)) | RCIN 1047467

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies : published according to the true originall copies 1623

-

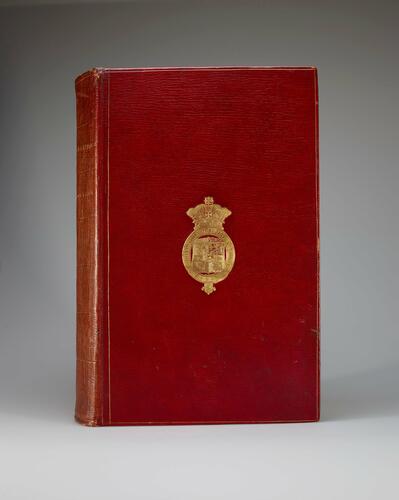

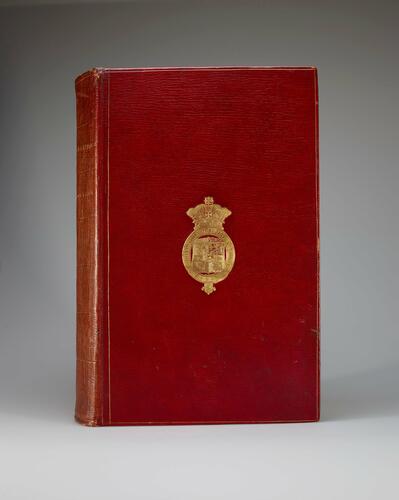

First Folio, re-bound in burgundy goatskin, probably c.1790. The original pages have been cut down and remounted.

The First Folio is the first printed collection of William Shakespeare’s plays. It was produced seven years after Shakespeare’s death when his friends and fellow actors, John Heminges (1566-1630) and Henry Condell (1576-1627), collected all his plays together, including ones which had never been published before.

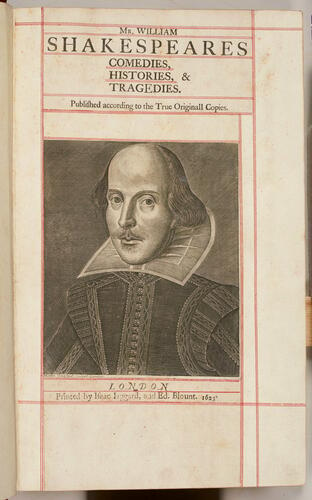

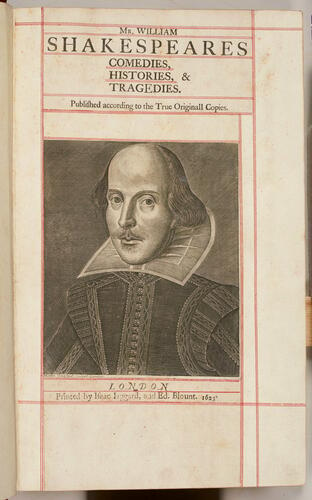

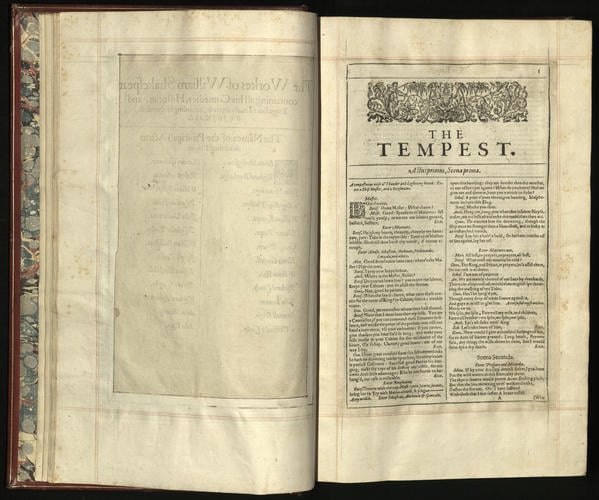

Without this book we would probably not have any texts of 18 of Shakespeare's most important plays, including Macbeth, Twelfth Night and The Tempest, which were published here for the first time. Furthermore, the engraved portrait of Shakespeare on the frontispiece by Martin Droeshout is one of the very few images of him with any claim to authenticity. The First Folio also contains important tributes to Shakespeare, such as Ben Jonson’s long poem which describes Shakespeare as “not of an age, but for all time!”

This collection of plays is therefore considered to be one of the world’s most important books. Far more copies of the Folio survive than of the Quarto editions (which contain single plays and were a smaller and more ephemeral format): around 235 copies are known to exist worldwide. It was reprinted in 1632, 1663 and 1685 and the editions are known as the Second Folio, Third Folio and Fourth Folio. This copy was acquired by George IV when Prince of Wales, c.1800 and is now kept in the Royal Library at Windsor, along with copies of the Second (RCIN 1080415) and Third Folios (RCIN 1047468).

More information

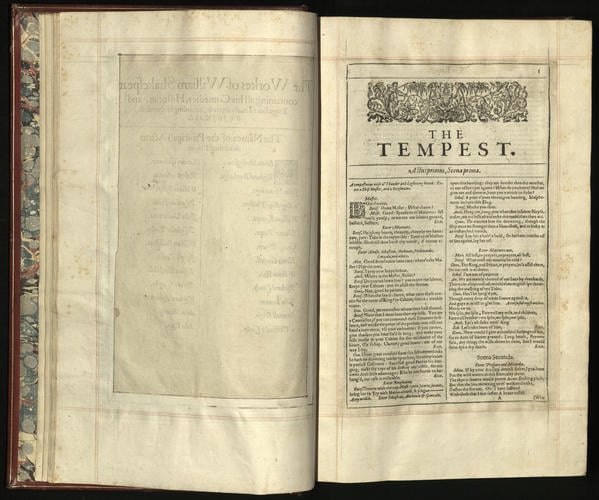

The publication of Shakespeare’s dramatic works began in 1594 when the Roman play Titus Andronicus was printed in the smaller, quarto format as a single play. Between 1594 and 1622, when the quarto edition of Othello was published, 19 separate plays by Shakespeare appeared in print (including Pericles, which was not published in the First Folio, but which would be included in the Third). The quarto texts were frequently based on prompt copies, or on the memory of one or more performers, and so were far from being perfect texts. And yet they sold. Shakespeare, while not hailed as the wonder of his age during his life, nor immediately after his death, was a good commercial prospect; between 1594 and 1623, 49 editions of his individual plays were published. However, as we now appreciate, 18 more plays, including some of Shakespeare’s best-known today (including Macbeth, The Tempest, Julius Caesar and Anthony and Cleopatra) had yet to appear.

Two publishing ventures prepared the ground for what is known as the First Folio of Shakespeare, the first being the folio edition of the works of Ben Jonson, first published in 1616. The Jonson Folio contained all of his works thus far produced (he continued to write until 1640), and the folio format, generally used for Bibles, histories and the like, gave them the status of serious literature, rather than the lowly status implied by the more ephemeral quarto format. The second venture was 10 quarto editions of Shakespeare’s plays published by Thomas Pavier, the first three of which (the plays we now call Henry VI part II and III, and Pericles) were published together, with separate title pages but with continuous page signatures (serving a similar function to page numbers to guide those binding the book).This had not been done before and suggests that Pavier may have been endeavouring to produce something that could be bound together as a collected works volume.

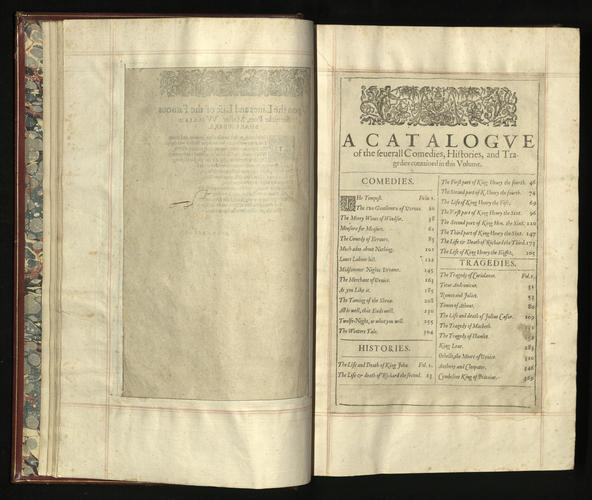

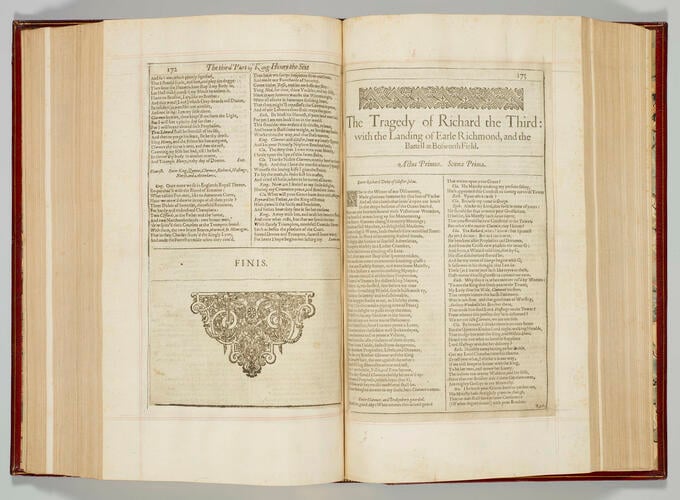

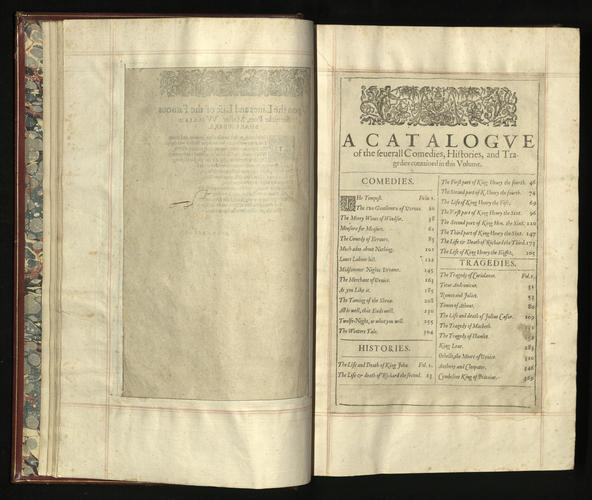

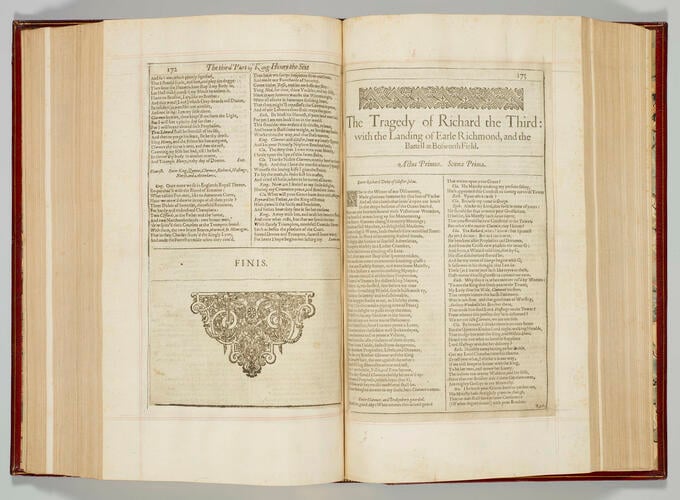

With these precedents available, in 1623 Shakespeare’s two acting colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell masterminded the publication of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies Published according to the True Originall Copies. To compile the collection, they needed to acquire the rights not only for the unpublished plays held by the King’s (previously the Lord Chamberlain’s) Men (the theatre company to which Shakespeare belonged and for whom he wrote), but also the rights for all the plays that had been previously published in quarto. This was not always straightforward: for example in the case of Troilus and Cressida, which is not in the table of contents in the First Folio, and yet appears in most extant copies. This is most probably because negotiations for its permissions went on so long that the publishers decided not to include it (and thus it does not appear on the contents page, where the plays are laid out by genre – Comedies, Histories and Tragedies), but were later able to insert it, without pagination, between the Histories and the Tragedies.

The First Folio was published by the father and son team of William and Isaac Jaggard, and Edward Blount. William Jaggard had been active in the London book scene since 1594, and with the works of Shakespeare in particular since 1599 when he published The Passionate Pilgrim, an anthology of poems attributed to Shakespeare. He was later involved in Pavier’s attempts to publish the collected works in quarto, and from 1621 he began work on producing the First Folio. He died in early 1623 and passed the task of seeing the Folio through the press to his son Isaac. Edward Blount was a stationer based in St Paul’s churchyard, the centre of the London book trade, where he worked from the 1590s onwards, specialising in translations of foreign literature.

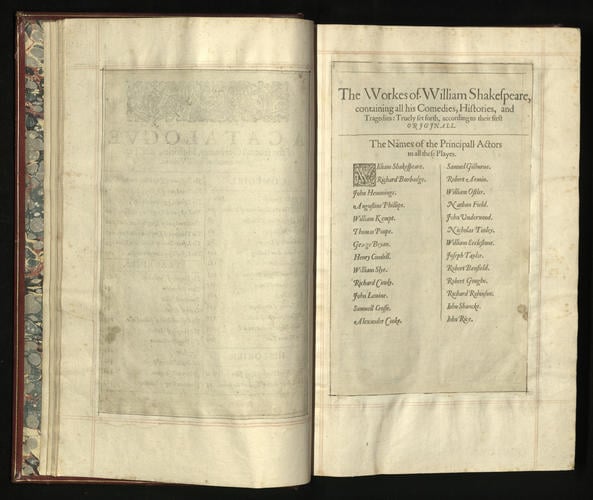

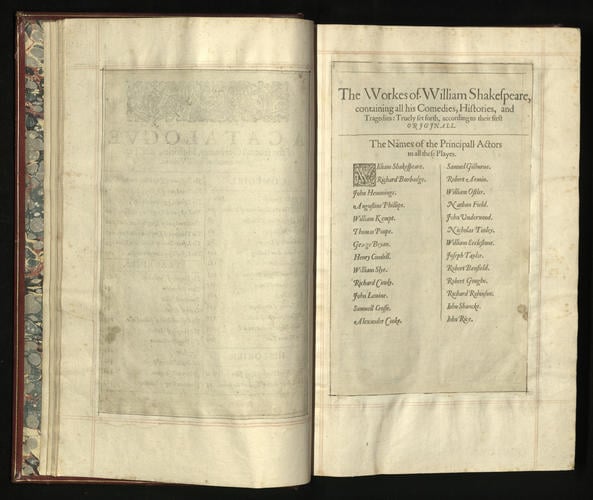

To introduce the collected plays, the First Folio contains several pieces of preliminary material, known as paratext. Probably most famous is the portrait on the titlepage by Martin Droeshout (which appears in three slightly different states), one of the few portraits of Shakespeare with any degree of authenticity (the short poem by Ben Jonson usually facing the portrait, but missing in the royal copy, states: ‘This Figure, that thou here seest put, / It was for gentle Shakespeare cut’). Heminges and Condell also wrote a fulsome dedication to their patrons, William Earl of Pembroke, and Philip Earl of Montgomery, but were rather more to the point with their address to ‘the great Variety of Readers’ who they anticipated ‘will stand for your privileges … to read, and censure. Do so, but buy it first’. Poetical tributes included two poems by Ben Jonson, one relating to the portrait, the other, longer work, praising the dead playwright as ‘Soule of the Age’ and immortalised by his works ‘Thou art a Moniment, without a tombe / And art alive still, while thy Booke doth live’ (a neat piece of advertising!); further eulogies were added by the less well-known poets, Leonard Digges, James Mabbe and Hugh Holland. The publishers also included a catalogue of the plays included in the Folio, divided by genre (Comedies, Histories and Tragedies), and the names of the principal actors in the King’s Men.

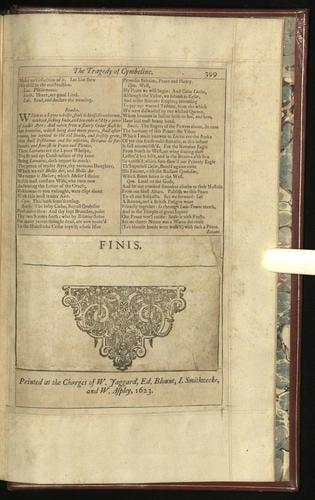

36 plays were included in the First Folio, 18 drawn from printed quarto editions, 18 from manuscript copies. These varied considerably in quality; the earlier plays derived from manuscript were printed from fair copies made by Ralph Crane, a professional scribe employed by the theatre company. His texts are distinguished by clear scene and act divisions, stage directions, and character lists, and he was responsible for the First Folio version of the texts of The Tempest, Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Winter’s Tale, and possibly Measure for Measure and Cymbeline. Other plays were typeset from so-called foul papers (original draft copies from the playwright) – All’s Well That Ends Well, Coriolanus, Henry V, and Twelfth Night are some of the plays that came from such a source. The final manuscript sources were fair copies from foul papers, often annotated to make prompt copies for use in the actual production of the play. These sources would also have been used for producing the earlier printed quarto editions, whose text therefore also varied considerably. For example here is the opening of Hamlet’s first soliloquy (Act I scene 2) from the 1st and 2nd quartos:

"O that this too much griev’d and sallied flesh / Would melt to nothing, or that the universall / Globe of heaven would turn al to a Chaos!" [1st quarto, 1603]

"O that this too too sallied flesh would melt, / Thaw and resolve it selfe into a dewe, / Or that the everlasting had not fixt / His cannon gainst seale slaughter "… [2nd quarto, 1604/5, almost identical to the First Folio text]

The First Folio rendition fixed the text to what we are now used to reading:

"Oh that this too too solid Flesh, would melt, / Thaw, and resolve it selfe into a Dew: / Or that the Everlasting had not fixt / His Cannon ‘gainst Selfe-slaughter"

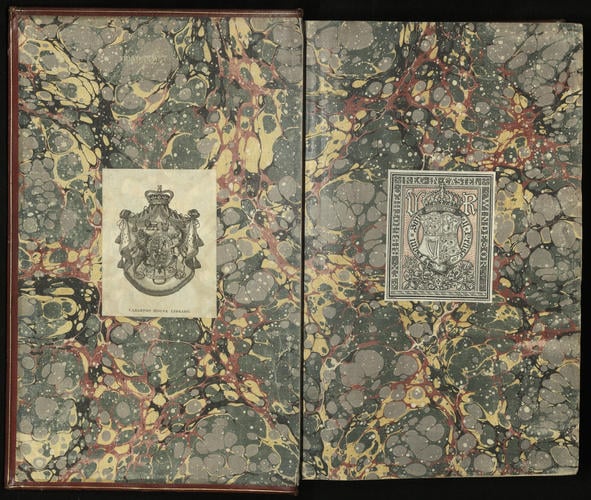

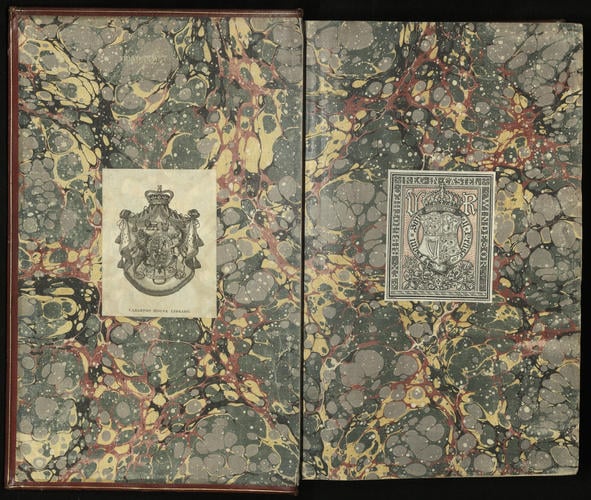

The Royal Library copy of the First Folio is what is known as a sophisticated copy, that is, one made up with leaves from multiple copies, or otherwise cleaned up. This habit grew from the late 18th century when the First Folio became a ‘must have’ book for collectors, and the fashion was to own a clean perfect copy. The titlepage and final page (the last page of Cymbeline) are each made up of three separate units pasted to a new leaf; the titlepage comprises a copy of the third state of the portrait, and two sections of facsimile letterpress (the title and the printers’ information). while the poem on the opposing page by Jonson on the portrait is missing entirely. The remainder of the text is made up from genuine Folio leaves but derived from several different copies, which we can tell from various indications - the differing watermarks in the paper, the general appearance of the pages, and in one case, extensive annotations on both sides of an individual leaf (leaf ff1), many of which are changes to or insertions of punctuation, in a style which does not appear elsewhere in the volume. The other notable piece of annotation appears at the end of Othello (leaf vv6) where a different hand has written in pen: ‘Fortune and nature did agree noe woman / should be fitt for / mee’ and ‘Honnorable Venarabl’. All pages have been cropped to the edge of the text and remargined (it is not known when this was done). The late addition of Troilus and Cressida appears in its usual place between the end of the Histories and before the Tragedies (thus between Henry VIII and Coriolanus). It was acquired by George IV, when Prince of Wales, probably not later than 1800, for his personal library at Carlton House in London. This library was transferred to Windsor by the 1830s as one of the foundation collections of the present Royal Library. It is not known precisely when or from where he acquired it (it does not appear in any archival bills or other documents) and the one previous ownership mark in the volume has been fairly vigorously erased. Its binding, in plain red burgundy goatskin, with minimal tooling, has no older ownership clues to offer either.

Its acquisition by purchase or gift by the Prince of Wales is consistent with his other purchases of Shakespeare’s works for his library, his acquisition of engravings of actors in Shakespearean roles for his print collection, and with his interest in drama in general. Shakespeare had been one of the few English authors included in his school curriculum, and once in possession of his own library he acquired several contemporary editions: a first edition of Johnson (1765), Johnson-Steevens (1778, 1802), and Johnson-Steevens-Reed (1813), as well as theatrical versions adapted from Shakespeare’s originals by the actor-manager John Philip Kemble and purchased from the Theatre Royal. These were intended both for Carlton House, and for the smaller library collection kept in the Pavilion at Brighton. He was not known as a serious book collector like his father George III (who also owned a First Folio, now in the British Library, and a Second Folio previously owned by Charles I, still in the present Royal Library, RCIN 1080415), and his collection was mainly contemporary rather than antiquarian. However, from other purchases (such as his second edition of Jonson’s Folio, published 1640, or his collection of 17th-century military volumes) we can see that he did not disdain older volumes when they suited his purpose. His knowledge of Shakespeare was attested by Samuel Ireland in 1795 when Ireland took his newly-discovered cache of Shakespearean papers (later established to be forgeries created by his son William Henry Ireland) to Carlton House to show them to the Prince of Wales. W.H. Ireland’s account in his Confessions (1805) describes that the prince examined them ‘with the strictest scrutiny’ and also that he

"questioned him [Samuel Ireland] on every point with an acuteness which he had never before witnessed from the learned who had inspected the papers, but he also displayed a knowledge of antiquity, and an intimate acquaintance with documents of the period of Elizabeth, which Mr. Ireland had conceived was confined to such individuals only as had made that particular subject the object of their study". (Confessions, p.218).

Further reading

Thomas Frognall Dibdin, The Library Companion, 2 vols (London: Harding, Triphook, and Lepard, 1824), vol. 2, p. 409

William Henry Ireland, The Confessions of William-Henry Ireland (London: Thomas Goddard, 1805)

Sidney Lee, Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies: … a census of extant copies (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902), p.30 (no. LXVI)

Eric Rasmussen and Anthony James West, The Shakespeare First Folios: a Descriptive Catalogue (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 171-175 (no.42)

Emma Smith, The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2015)

Emma Smith, Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book (Oxford: University Press, 2016)

Anthony James West, The Shakespeare First Folio: The History of the Book. Volume I, An Account of the First Folio Based on its Sales and Prices, 1623-2000 (Oxford: University Press, 2003)

Anthony James West, The Shakespeare First Folio: The History of the Book. Volume II, A New Worldwide Census of First Folios (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 129-130 (no. 42)Provenance

Acquired by George IV when he was Prince of Wales and held in his Carlton House Library

-

Creator(s)

(printer)(printer)Acquirer(s)

-

Measurements

40.4 x 25.6 x 6.8 cm (book measurement (conservation))

Category

Alternative title(s)

First Folio