-

1 of 253523 objects

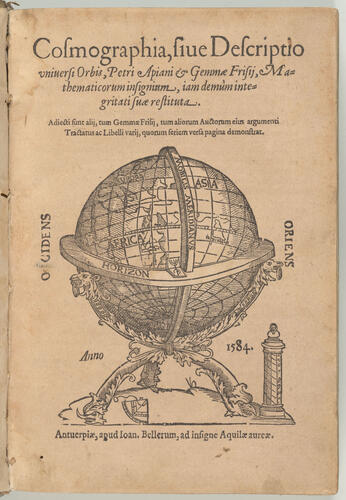

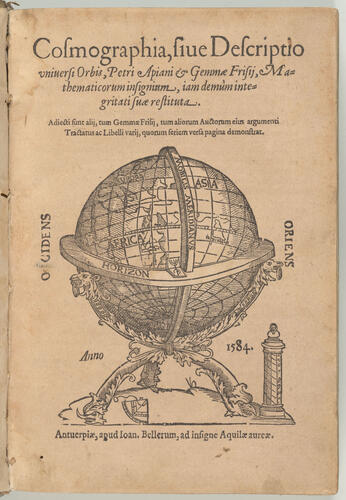

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis 1584

24.5 x 16.9 x 4.5 cm (book measurement (conservation)) | RCIN 1046807

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

Peter Apian (1495-1551)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta 1584

-

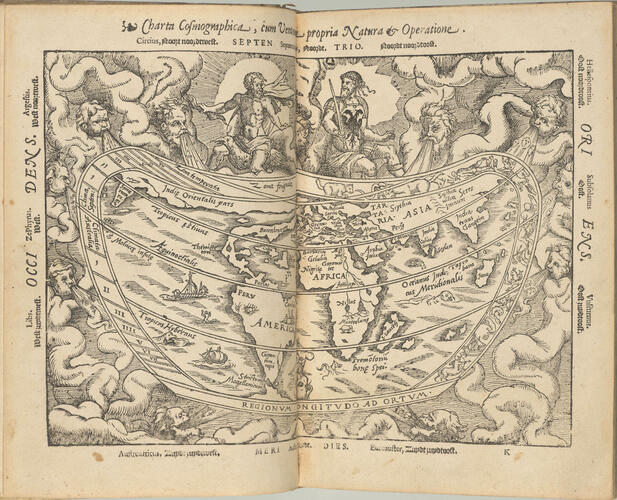

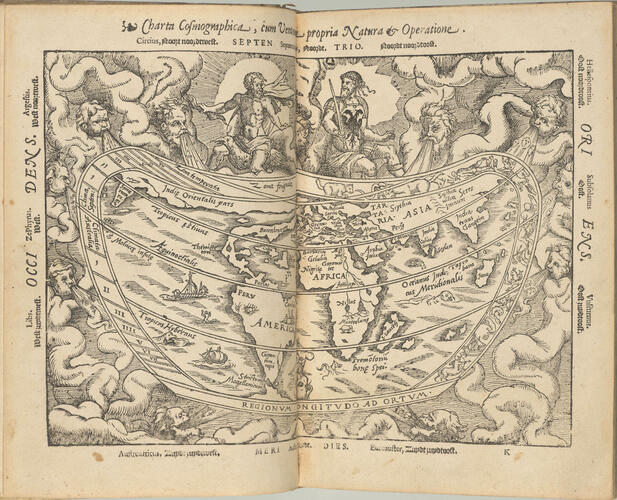

Peter Apian (1495-1551), professor of mathematics at the University of Ingolstadt, is best known as the author of a highly influential digest on cosmography: the study of the universe and the place of earth within it. Cosmography was intertwined with geography and astronomy from antiquity until the early modern period. However, as European explorers began to report back about their voyages along the Atlantic coasts of Africa and the Americas, the scholarly understanding of earth in relation to the fixed heavens began to shift. Gradually, its study was seen as a distinct discipline from that of earth as inhabited land, and therefore cosmography, geography and astronomy slowly became distinct disciplines. Partly to clarify the different aims of these fields, Apian published his work for the first time in 1524 (Cosmographicus liber Petri Apiani mathematici studiose collectus, Landshut: Johann Weissenburger). It presented an amalgam of old astronomy (Ptolemy’s geocentric model), astrology, cosmography, cartography, and instruments to measure the earth and the heavens.

As Cosmographia responded to the contemporary curiosity about new understandings of the earth, it went through many revisions and additions in the course of the sixteenth century. In this respect, the contribution by Apian’s former student, Gemma Frisius (1508-1555), was pivotal. The Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument-maker first revised his teacher’s work issuing a ‘studiously corrected’ edition of Cosmographia in 1529, having sensed its potential. In 1533, Frisius released a new version with extensive explanations on how to use the scientific instruments described and added his own writings to Apian’s work. This version consolidated Cosmographia’s success: it saw more than 30 editions as well as translations into French, Spanish and Flemish, and incorporated further works by Frisius and others (for a full list of editions, see Editions of Cosmographia | MHS Oxford). The edition housed in the Royal Library is that of 1584, printed in Antwerp by Jean Bellere. The works by other scholars included in this volume are:

Francisco López de Gómara, Situs ac descriptio Indiarum (pp. 160-166)

Gerónimo Girava, Situs et descriptio Indiarum (pp. 167-187)

Gemma Frisius, Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (pp. 193-208)

Gemma Frisius, Vsus annuli astronomici (pp. 209-222)

Gemma Frisius, De vsu globi (pp. 223-248)

Johann Schöner, Coelestis globi compositio (pp. 249-281)

Gemma Frisius, De radio astronomico et geometrico liber (pp.281-282)

Georg von Peurbach, Tabula gnomonica (pp. 282-347)

Johann Spangenberg, Fabrica baculi astronomici (pp. 348-349)

Sebastian Münster, De principiis geometriae (pp. 350-353)

Gemma Frisius, De astrolabo catholico liber (pp. 354-478)

Cornelius Gemma, Carmen panegyricum (p. [479]).

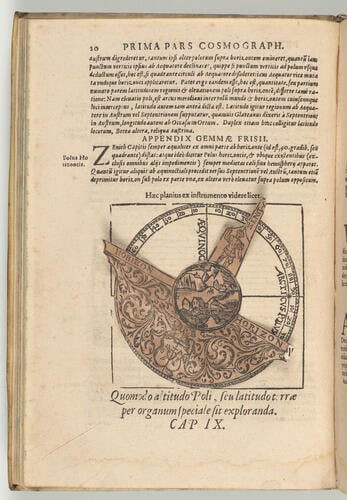

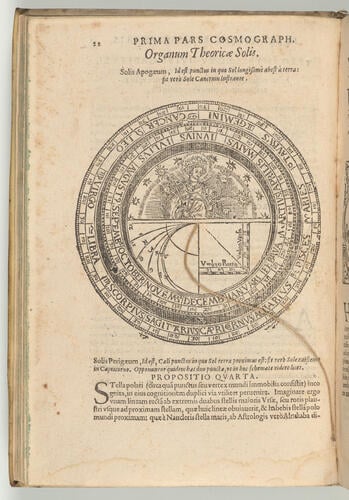

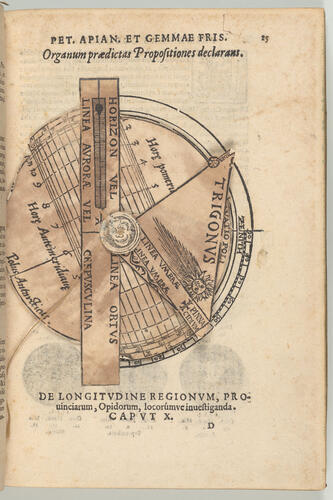

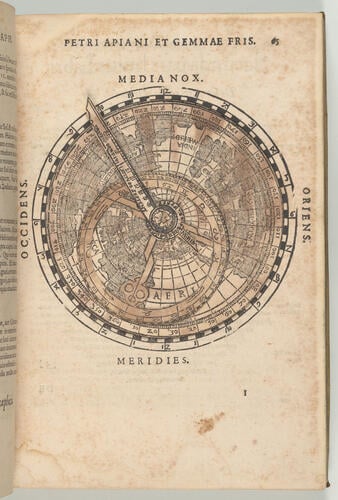

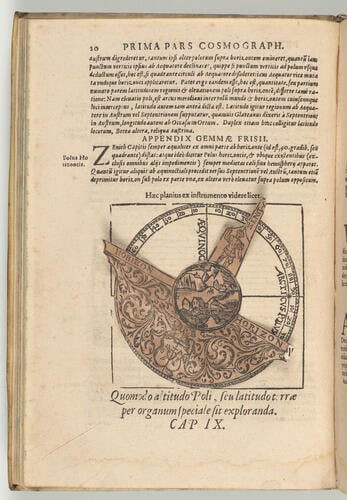

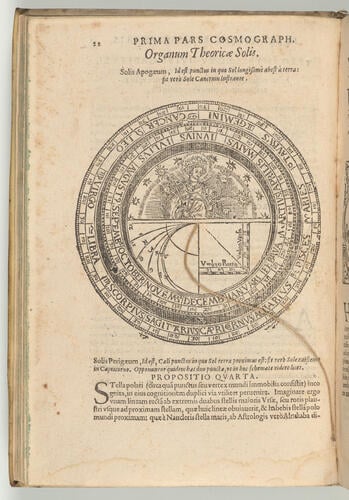

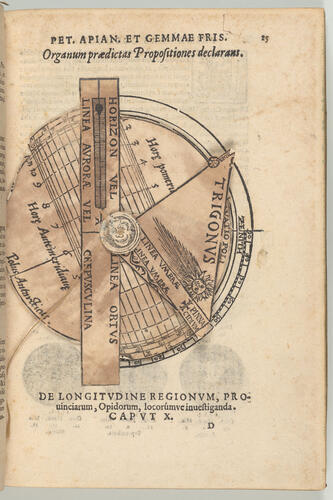

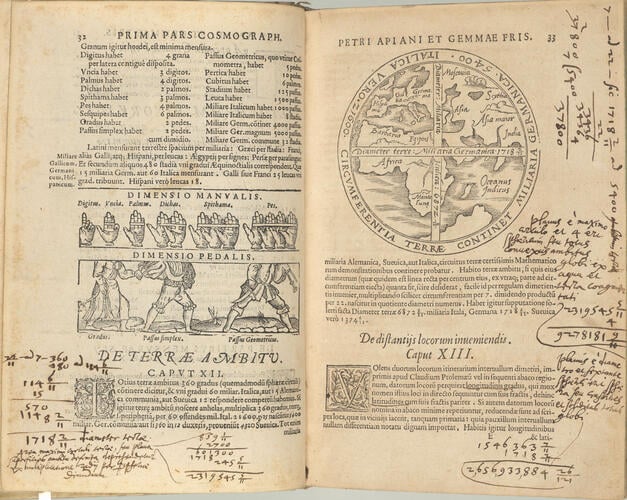

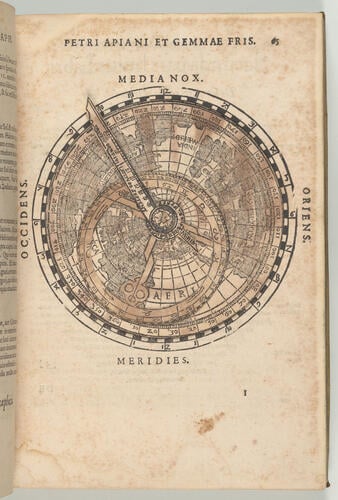

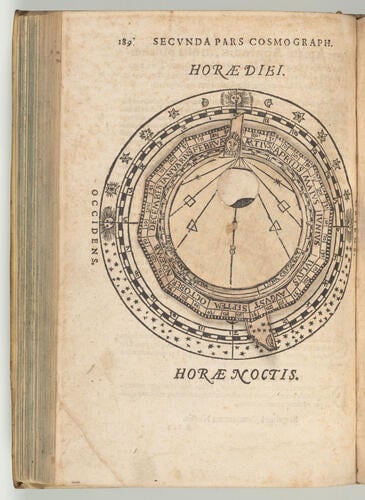

While Cosmographia was one of many sixteenth-century publications engaging with cosmography, cartography and mathematics, its distinguishing feature was the extensive use of volvelles, movable paper instruments. Printed as woodcut illustrations, the volvelles are stacked up and pinned in the centre to rotate individually. In Cosmographia, they allow readers to identify the geographical coordinates of a place, the hours and height of the celestial pole, the position of the Sun and the Moon at different times of the year, and the hours of day and night. The instruments become more difficult to use as the text progresses, demonstrating that Apian guided his readers through increasingly complex concepts. It is hardly surprising that he addressed them as ‘tyrunculi geographiae’ (little geography apprentices): Cosmographia was an educational tool for self-taught amateurs. Thanks to the instruments, early modern readers who had no professional training in astronomy, geography or mathematics could not only experiment with the ideas described in the book but also participate in the new scientific discourse. The very action of using the volvelles merged the physical with the intellectual, forming an important new category of enthusiastic learners.

Furthermore, the volvelles and maps, which drew on the discoveries of explorers and developments in cartography, were aesthetically pleasing – another reason for Cosmographia’s popularity with both experts and amateurs. The visual element of new scientific writings cannot be underestimated. The title page of Cosmographia displays a large globe accompanied by cutting-edge astronomical instruments. The inclusion of a map of the New World – originally published in Martin Waldseemüller’s Cosmographiae introductio (Saint-Dié: Walter and Nikolaus Lud) in 1507 – raises the work’s significance as an early source of observations about America’s First Nations and their land.

Each of the volvelles of the Royal Library copy was printed on separate pieces of paper and then lined with reused paper. The oxidation of adhesives has led to discolouration. The reused paper contains printed and manuscript fragments: the printed text has now been identified as coming from an early copy of Gregory the Great’s commentary on the Song of Songs, while the manuscript fragment is from a fifteenth-century copy of Gregory the Great’s Regula pastoralis (pars secunda, cap. vi), written in secretary script.

Binding description

Laced-case vellum on six cords. Spine flat with ink titling. Endpapers of plain paper.Provenance

Acquired by William IV, 1830-1837. Previously owned by Philipp Ludwig II, Count of Hanau-Münzenberg (1576-1612); sold from the collection of Friedrich Gottlieb Julius von Bülow (1760-1831) in 1836.

-

Creator(s)

(publisher)(printer)Acquirer(s)

-

Measurements

24.5 x 16.9 x 4.5 cm (book measurement (conservation))

Markings

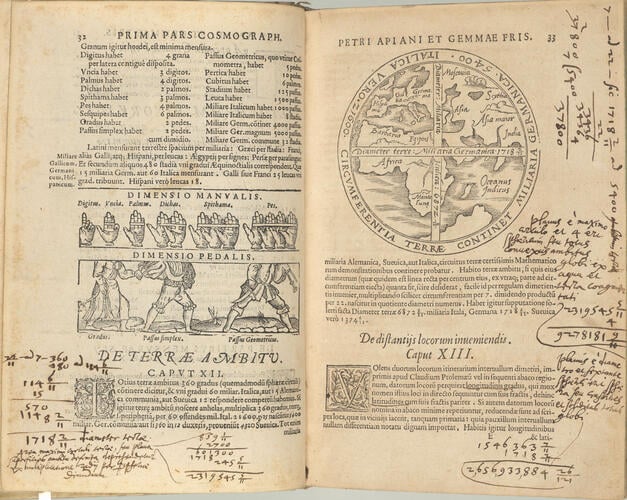

annotation: Notes in Latin and calculations [latitudes and longitudes] in a late sixteenth-century or seventeenth-century hand (no later than 1640s). [pp. 32-33]

Alternative title(s)

Cosmographia, sive descriptio universi orbis Petri Apiani et Gemmae Frisii, mathematicorum insignum, iam demum integritati suae restituta. Adiecti sunt alii, tum Gemmae Frisii, tum aliorum auctorum eius argumenti tractatus ac libelli varii, quorum seriem versa pagina demonstrat.

Place of Production

Antwerp [Antwerp province]